The Fourteenth Sunday after Pentecost, Year A, 2017 – Exodus 12:1-14; Romans 13:8-14; Matthew 18:15-20

For my birthday this year Sarah gave me a calendar she made full of family photos over the years. In one of them the three kids (Robbie isn’t around yet) are standing on our front doorstep, backpacks on their backs. It’s the first day of school; for Sarah, the very first day of school ever: Junior Kindergarten. She’s just a tiny tyke, not even 4 years old yet. She’s got her favourite T-shirt on with the three happy whales on the front and she’s looking brave. She tugs at my heart, that little not-quite-four-year-old, setting out on her new beginning.

September is a new beginning, in the rhythm of our lives. The lazy days of summer are over; for all the kids and all the teachers, it’s the first week of school. Wycliffe was buzzing this week with new students, their eagerness for this new adventure, their energy, maybe a little trepidation, too.

This month marks for us, our Archbishop said this week, the ‘real’ beginning of the year.

I am not sure whether the Archbishop intended it or not, but he is echoing God.

The Lord said to Moses and Aaron in the land of Egypt, “This month shall mark for you the beginning of months; it shall be the first month of the year for you” (Exod 12:1).

In Egypt the Israelites were struggling, treated like slaves, used as forced labour to build Egyptian cities, their boy babies thrown into the Nile. The Israelites groaned under their slavery, and cried out (Exod 2:23). And God heard their cry. Out of the flames God speaks to Moses and gives him this command: “Go to Pharaoh and say to him, “Thus says the Lord, the God of Israel: let my people go.”

Out of bondage in Egypt God is calling his people, out of slavery to powers that are not good and are not God, out of the city that does not know God, so that they may be his people. “Thus you shall say to Pharaoh,” God says to Moses. “Thus says the Lord. Israel is my firstborn son. Let my son go, so that he may worship me.” Let my people go.

It is an urgent call. “This is how you shall eat it,” this lamb of the Passover, God says to Israel: “Your loins girded, your sandals on your feet, and your staff in your hand, and you shall eat it hurriedly. It is the Passover of the Lord.” It is an urgent call—because behind there is only servitude to gods that are no gods, behind there is the angel of death. Eat it hurriedly, your sandals on your feet. This place is no place to stay. It is an urgent call.

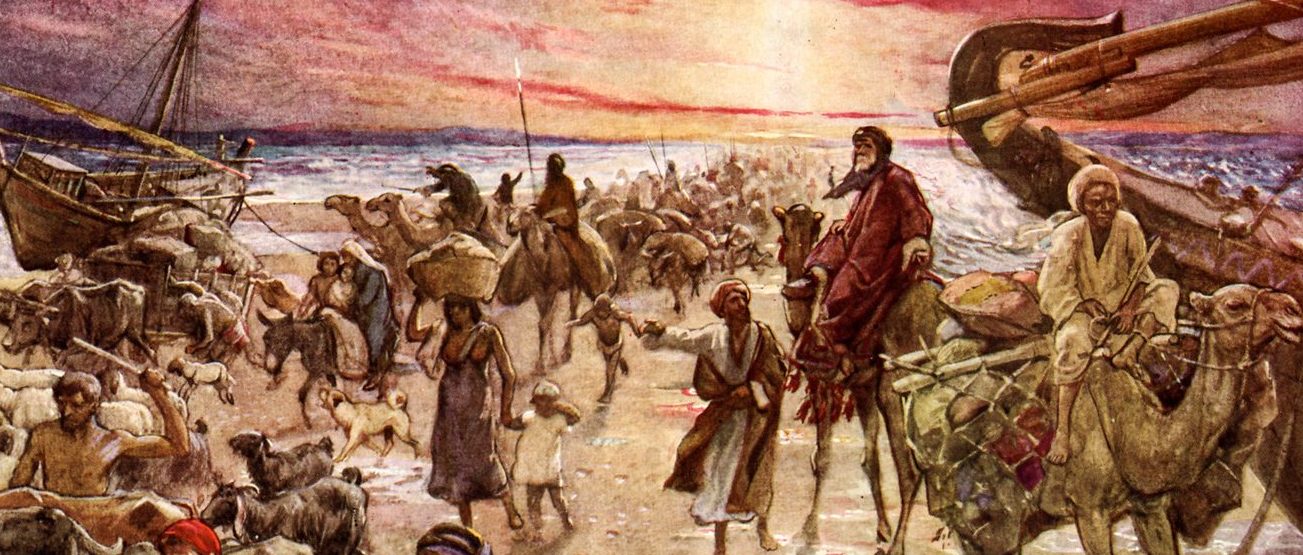

It is a costly call. We have leaped (in our lectionary’s infinite wisdom) straight from the burning bush last week to the Passover today, straight from chapter 3 to chapter 12, and so we have missed the struggle. Moses’ courage, standing in front of Pharaoh time after time though he is no good at this sort of thing; Pharaoh’s hardness of heart; nine great plagues sweeping over the land: blood and frogs and gnats and flies and pestilence and boils and hail and the dread locust, and darkness so thick it is tangible. It has been hard to get to this place, this cusp of the new beginning, and it is going to be harder still. This night, this very night, there will be death, and flight, and the armies of Pharaoh, horse and chariot, pounding toward the people of God trapped at the edge of the sea.

This is how you shall eat it: your loins girded and your staff in your hand. To be called out takes courage and endurance and a readiness to go—to leave behind the city, the pagan city, the familiar city, to go into the unknown country

It is an urgent call; it is a costly call. And it is the call that saves. By the blood of the lamb Israel is saved this night. “It is the Passover of the Lord. For,” God says, “I will pass through the land of Egypt that night, and I will strike down every firstborn in the land of Egypt, human beings and animals; on all the gods of Egypt I will execute judgement: I am the Lord. The blood shall be a sign for you on the houses where you live. When I see the blood, I will pass over you.” This is the call that saves—from the judgement of God on the gods that are no gods, the

judgement on Pharaoh’s hardness of heart.

This lamb of the Passover is God’s call out of death into life. This day is the beginning of days.

Throughout their generations Israel celebrates this day, to this day they celebrate it, Passover, the judgement and the salvation and the call of God.

We, too, have a Passover. We too have a lamb who is slain, the judgement and the salvation and the call of God. That Passover long ago, that people called out by the mercy and justice of God is for us a sign and more than a sign. That people called out by the Passover lamb to be Israel, the people of God, has borne for us Christ Jesus, son of Abraham, the lamb of God. His blood now a sign for us; his blood the blood that saves. That is what we celebrate every week, here in this place. Through the Red Sea brought at last! We too have been given a share in the worship of God; we too have been given a share in life.

And this means we have been called out. It means a new beginning. “This is how you shall eat it,” this Passover lamb, “your loins girded, your sandals on your feet.” We are called out every bit as much as the Israelites were in the days of Pharaoh, called out of bondage to gods that are no gods, called out of the pagan city, into the worship of God. By the great grace of God Israel’s salvation has been made ours too, so that we too may worship the one God, Lord of all. So that we too may be God’s people, grafted in Christ Jesus into the chosen people. And that means being God’s people. It means leaving behind the old gods, discovering a new home.

I think this is a particular challenge for us Anglicans.

My father’s family is Brethren in Christ. They know (or knew—things have changed in the denomination) about being “called out.” Everything about their lives when my Dad was growing up was different from the people around them; the small things of their lives were a sign of their Christian identity. My father wore plain-clothes to school; his sisters wore prayer bonnets. They did not drink or dance or smoke or play cards. They did not go to movies. They could not even take part in the school Christmas pageant.

They understood themselves to be called out, distinct from the secular culture around them, defined by Christ, stepping out into a new beginning in Christ that visibly shaped their whole lives.

“You know what time it is!,” the apostle Paul said to the new Christians in Rome. “Now is the hour for you to wake from sleep!…The night is far gone; the day is near: let us put off the works of darkness and put on the armour of light. Let us walk honourably, as in the day, not in partying and drunkenness, not in hooking-up and promiscuity, not in quarreling and jealousy. But put on the Lord Jesus Christ.”

This is what the BIC community believed and lived. With their plain-clothes they sought to put on the Lord Jesus Christ.

For Anglicans it is different. We have never seen ourselves as set apart from the society around us as Puritans and pietists do. On the contrary, we are right at home.

We are a church founded by the King. Our boundaries are the parish. The whole neighborhood in which we live is part of the church, in the Anglican view; there is no ‘secular’ place distinct from the church. In the age of Christendom, there was a sense in which this was really true.

But it is just not true anymore. It is still the goal—that the whole neighborhood might come to know and love Jesus Christ. But it is not the fact on the ground. To believe in Christ, to know he is the lamb who has given his life to bring us out of bondage to gods who are no gods into life—life that is turned to the one true God—to know and to love Jesus Christ is now to be different.

It requires, in our context, actually a new beginning. To step out of the old world, into the new. To love and to follow Jesus is now to be different.

And so we need to look different: visibly people who belong to Christ.

How to do this? Rod Dreyer, author of The Benedict Option, and others are talking about intentional Christian community. I think they are right. But I want to say too that it starts right here. We have intentional community at our fingertips right now, in the life of the church.

It starts right here, by being called out on a Sunday morning when the rest of the city is in bed or reading the paper or at hockey with the kids or at brunch; by being called here on a Sunday morning instead.

It starts right here: by hearing here the Word of God; really hearing it as the most important and most beautiful and most challenging word in our lives and carrying this word on our hearts every day.

It starts here: by coming here to meet Jesus Christ and to be formed in him, and going from here with his grace on our lips.

It starts here: by coming here on a Sunday as to a feast, the feast we have been waiting for all week long, the great banquet of the lamb. Coming here with joy to the joy at the centre of our lives.

This day shall be the beginning of days for you.

Alleluia. Amen.