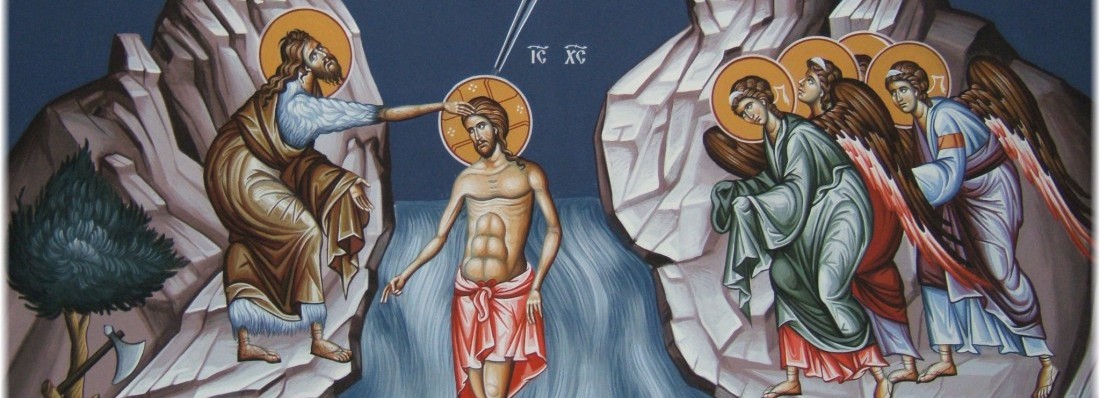

The first Sunday after the Epiphany, Year B, 2015 – Genesis 1:1-5; Psalm 29; Acts 19:1-7; Mark 1:4-11

It is wonderful to be back at St. Matthew’s, after 7 months away on sabbatical. We worked hard in Strasbourg, France; slept a little longer each night than usual; got some exercise, and were blessed in many ways. We also found a wonderful Anglican church in Strasbourg – St Alban’s – about the same size as St Matthew’s, and filled with people from around the world – Madagascar, England, Pakistan, Sierra Leone, Canada, France, Nigeria, the United States. I prayed for you every week, knowing that we were so close to one another in the Lord.

On this first Sunday after the Epiphany, when we traditionally celebrate the Baptism of Jesus, I am reminded of one of the baptisms we had at St. Alban’s. It was the small daughter of a Nigerian family, little Cecelia. I had forgotten, I guess, what a big deal this is in that Christian culture: a large extended family presence, beautiful clothes for all, videos (something I hate, but there you are), and then food and feasting for everyone afterwards – cakes, snacks, the whole bit. What’s that all about?

It’s not exactly what happens to Jesus in the river Jordan. What do the two possibly have to do with each other? Which presses us to the major question: what is Jesus doing getting baptized in the first place? It’s a question that the early Christians themselves asked. In Matthew’s recounting of the episode, which we just heard from Mark’s Gospel, we read that John the Baptist “would have prevented” Jesus from getting baptized: “I need to be baptized by you, and do you come to me?” (Mt. 3:14). It’s a question everybody asks, and should. After all, baptism is for… well, what? We’ll come back to that in a moment. But for now we can simply quote Paul: baptism, he says in Romans, is a form of “dying to sin”. And he goes on, “do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? Therefore, we have been buried with him by baptism into death, so that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, so we too might walk in newness of life” (Rom. 6:2-4).

Whatever baptism is for us, it is at least this: being joined with Christ, and thus sharing in his victory over sin and death.

So I ask again: what is Jesus being baptized into? He who has no sin and is life itself? How can the Son of God — God himself, we must say — be thrown into the midst of the experience of our being thrown into the midst of his experience, if you will? It is mind-boggling, confusing, running round and around.

But it is actually part of the whole fabric of God’s life with us in Christ, if we stop and think about it. God, in Christ, weeps with our tears (Lazarus; Jn. 11:35). God in Christ prays with our prayers of desperation (Psalms on the Cross; Mk. 15:34/Ps. 22:1). Most astonishing, perhaps, is the fact that God in Christ eats himself in the form of our eating him. That’s what the Last Supper seems to indicate, as he shares the bread and wine – this is my body and my blood – and then eats and drinks himself thus sharing himself (cf. Mk. 14:22-24).

So Jesus is baptized, as it were, with the baptism with which we are baptized. (and cf. Mk. 10:38!!) At least that. And if we look at baptism from our point of view – for God is sharing our point of view here, by the river Jordan – what do we see?

I assume that some you here know the British author P.D. James. She died barely 6 weeks ago at the age of 94. She was considered perhaps the pre-eminent mystery novelist of her generation in Britain, and was avidly read by people around the world. She was also a committed Anglican Christian, and in fact many of her stories are loosely tied to churches and seminaries and so on. In 1992 she published her only non-mystery novel, Children of Men, which was made into a major film in 2006. The film is very poor, the novel magnificent, and let me say something here about its plot, which is highly relevant. Children of Men is about a future, not far away, when, for some mysterious medical reason, all the males of the world become sterile. A virus? Some weird mutation? Nonetheless, human generation has come to an end, and the human race is dying out. James imagines what a society like this would look like, in this case within Britain: it has become somewhat fascistic, in order to maintain control. Older persons, who are of course quickly becoming the preponderant majority of the population, have no one to care for them, and are carted off in boats at a certain cut-off age to be drowned in the North Sea. Those who are younger still, have nothing to live for, and have descended into bands of listless or immoral roving pleasure and cruelty seekers – a country of uncontrolled, but slowly diminishing motor-cycle gangs and the quietly disappearing. The human race is running down in simmering but slowly evaporating violence and desolation.

But the center of the plot is the sudden discovery, now a couple decades after the onset of male sterility, of one woman, a young woman who is… pregnant! It is astonishing, and raises all kinds of questions: has there been a mutation back to fertility? Where? Who? How far? More immediately, what does this new fact mean for the social order, an order that has adapted to death and disappearance? For those who are benefiting from it, somehow? Those in power? There are, we realize, many people in this twisted world for whom this new child is a threat, not a joyous miracle. The pregnancy, thus, is a guarded secret, and hidden within a small group of resisters to the present order of death. More to the point, though, this small group, hiding in the woods, protecting the young pregnant mother and her child, are Christians, by now a small, isolated, and prohibited religion. There they are, beleaguered and pursued, surrounding a potential miracle of life.

The pregnancy is discovered by the authorities, they seek to capture and kill the mother and her friends, and the tension-filled story develops and races to its end. And the end itself? It is a healthy birth, squirreled away in the woods… and then, then, a quiet baptism. That is the end.

A baptism. I’m not in a position to say what James’ main point in this novel was. Probably many points. Certainly, she was concerned by the developing cultural rejection of procreation, the embrace of human death in so many ways, and on and on. At the root, though, I think she saw this: human beings are God’s creations, his creatures – hence the title, “Children of Men”, which is a phrase from the King James Bible, as in Psalm 90:3: “Thou turnest man back to the dust, and sayest, ‘Turn back, O children of men!”. It is for these creatures that God is God to us at all. It is to God and for God that we live at all. And the offering of ourselves to this relationship is the foundation for our love, that must necessarily give rise to new generations, to children, to their growth and formation. To a future.

The baptism at the end of the book, then, is bound up with this: hope. A hope that is strong enough to break down despair, threaten governments, upend chaos, bring new life. And that, I suggest, is what we are doing when we get baptized ourselves or bring our children into baptism’s embrace. We are entering into and being seized by hope.

An almost desperate hope, given what the world is actually like, and what we often face. But also a joyful, wondering and wondrous hope, just because of that; frightening and creative at the same time. To hope in the possibility of something new coming “from nothing”, as it were, is to indicate where this kind of hope is founded: the very life and act of God, who, after all, “creates from nothing”. In baptism, we enter the entire miracle of being itself – God has made me and this making is my self and the world’s! – we enter this, but now with eyes wide open.

So Jesus does this himself. After all, even a hope such as this could be mistaken; could be wishful thinking. So Jesus does this himself: he enters our hoping, he enters our deepest hoping, our hoping as children of God, not only of men – the Psalm reg. children of men and creation. God himself enters into the miracle of our becoming.

I want us to think about what this might mean. “In those days, Jesus came from Nazareth of Galilee and was baptized by John in the Jordan” (Mk. 1:9). If God enters our hoping – this reaching out to God in baptism, this hoping for God himself — what is happening? Is not the very thing we are reaching towards now given in our reaching itself? In desiring God, have we not already been given God? What we have here is a certain kind of “closeness”; indeed the strange closeness that explodes into life itself. Yes, “explodes”. When David says of God, “where can I go from your presence? in heaven you are there; in death you are there; beyond the sea you are there, in light and in dark, you are there” (Ps. 139:7-12), what he realizes in saying this is that, this is what it means to have been made by God, to be here at all! “Your eyes beheld my unformed substance, you made me in secret, my days are all in your book, formed before they yet were” (vv. 13-16).

Jesus is baptized. That means that the deepest thing we hope for is given already. This takes us back into the dizzying reality I mentioned earlier: God weeps with our tears; God cries out with our weeping; God eats himself in the form of our eating him. How close has God come? This close!

“Before you call, I will answer; while you are yet speaking, I will hear!” (Is. 65:24). The Baptism of Jesus is the fulfillment of all the prophets who, like Isaiah, yearned to say utterly, “Lo, this is our God; we have waited for him that he might save us. This is our God!” (Is. 25:9). Here he is! In Jesus’ Baptism, God answers us before we call. God is behind us before we are. God “goes before us” before we have moved.

And this is why we have nothing to fear in being faithful to the one who has made us and redeemed. For God gives himself as us as we give ourselves to Him. God is in our self-giving to him. No fear, no qualms, no obstacles in asking, praying, following, wagering all, for the sake of divine love.

I was so gratified to find out, while away, that St. Matthew’s is moving ahead with the possibility of refugee sponsorship. And today we are lucky to have Stacy Topouzova here to talk a little about this situation. Alright then: if Jesus came from Nazareth to be baptized by John in the Jordan, surely we have no fear in stepping out! For he is already in and present within our stepping out. But even more so, we can be among those who step into the fear of those who come here seeking a home, and allowing our baptisms to feed them with God’s presence. Teaching in Cairo this May, I was introduced to several hundred Syrian refugees the Anglican Church is helping in their long and frightening journey into safety. The grandson of someone just like them, Jewish in this case, I could not but feel something deep. “When Israel was a child, I loved him, and out of Egypt have I called my son”, God says in the prophet Hosea. But look, says God: in calling my “son”, I have called myself, because I have been with you even before you yourself we exiled, released, born, dead, and resurrected. I was baptized before you were.

Let us see where God will take us this year – each of us, in our work and family. All of us, here at St. Matthew’s, in our thirst to follow the Lord. Let us see, but let us see with open eyes and open hearts and boundless expectations. For the Baptism of Jesus is the Magna Carta of fearless hope, brazen risk for good, open embrace of love, extravagant discipleship.