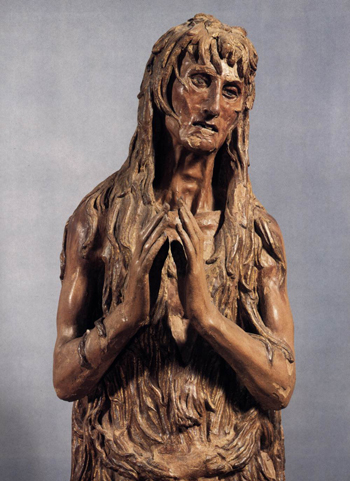

She stands, sorrow-wracked, clothed in rags. Her face is haggard; her eyes stare; her mouth is open in a word, or a cry. She looks for all the world like John the Baptist.

I first came face-to-face with the Penitent Magdalene in an almost-empty museum in Florence (the Duomo museum, under-visited—no lines; no tourist-packs—and full of treasures) and was transfixed. Such wildness of grief, fixed in wood. The eyes suddenly visionary, freed from the old demons, looking inward in some prayer too deep for words.

The Penitent Magdalene is, it turns out, a trope of medieval and early Renaissance art, but Donatello’s sculpture remains for me the most powerful. Perhaps it is because Donatello stands on the cusp of the Renaissance, and so his Magdalene is both other-worldly and powerfully human. Her grief is real, written in her cheekbones and the tendons on her arms, but it is also iconographic: her penitence representative; her prayer the prayer of all the saints throughout history. She speaks for me, as well as to me.

Mary Magdalene in this sculpture reflects the living faith of the church. She is penitent because she has been a prostitute; she prays because Jesus has freed her from the grip of sin. In the wildness that lurks in her body’s every line there is the memory of the seven demons that Jesus has cast out.

Much of this is not in the Gospels, precisely—and yet it is all there, pieced together in the devotion of the people from various stories. “Mary Magdalene,” Luke says in passing (8:2), “from whom seven devils had gone out,” a follower of Jesus along with the disciples and other women who have been healed. This mention comes right after the story of the woman who anointed Jesus’ feet: “Standing at his feet and weeping she began to bathe his feet with her tears and with her hair she dried them; over and over she kissed his feet and anointed them with oil” (Luke 7:38). The Pharisee, Jesus’ host, mutters: “If this man were really a prophet, he would have known what sort of woman this is who is touching him. He would have known that she is a sinner.” And Jesus says, “I came to your house and you did not even give me water to wash my feet. She has washed my feet with tears and dried them with her hair.…I tell you, her sins, which are many, are forgiven her; hence she has shown great love” (Luke 7:47).

Is she a prostitute? We are not told. But she is a “woman of ill-repute,” known in the city as a sinner (Luke 7:37). Prostitute is a good guess.

Is she the same woman as Mary Magdalene? We do not know, but right after her story, Mary Magdalene is named for the first time—Mary who has been freed from evil. In the reading of the early Christians, the connection is logical.

Later the story grows: according to medieval legend, after Jesus’ death and resurrection Mary, set adrift together with Lazarus and St. Maximinus (and other Christians) in a rudderless boat, without an oar, lands safely by God’s grace on the shores of France and becomes preacher and apostle, converting the pagans of (present-day) Marseille.

In France, Mary becomes a hermit. In the early Christian legends, she wanders 30 years in the wilderness in penitence for her sins. It is this Mary whom Donatello captures: Mary wandering gaunt and wild, her surprisingly powerful hands raised in prayer. No wonder, given the legends, that she looks like John the Baptist: this Mary is a preacher, proclaiming by her penitence the forgiveness of the Lord; announcing by her prayer the renewal of her life, this grace of God. This Mary is a prophet, stopping people in their tracks in the quiet of the museum; crying to all who pass by, “Prepare the way of the Lord.”

She announces something else, too, not just in Donatello’s rendering but in the grip her story has had on the imagination of the church. She announces a life changed by the love of God in Christ.

For this is the final thing about Mary. She is a woman who loves and is loved.

The Magdalen is there at the foot of the cross in almost every medieval painting of the crucifixion, beautiful and desolate, her arms raised in anguish toward the dying Christ, her long blonde hair falling to the ground.

“The one to whom much has been forgiven, loves much.”

We forget this perhaps in our competent age, as Simon the Pharisee forgot it then. We do not after all…surely…need to be forgiven. And yet there is a grief that rises in the heart for the things we have done and have not done, the world’s capacity—and ours—to harm. There is a grief in the heart. Mary loved Jesus because he loved her. In spite of her demons, and knowing them; in spite of her life, and knowing it, he came near. He touched her when no one else would, and cast the demons out of her soul.

Jesus loved Mary with the love of God, that sees the heart and loves still, loves and saves, calls to the heart to look up and grow glad and live.

All things are possible in the love of the Lord, even that many demons should be cast out. Even that a prostitute should become a prophet and a woman of no name from Galilee speak the name of Jesus in France.

All things are possible in the love of Christ.

It is Mary Magdalene who first sees the risen Lord. She is there at the empty tomb in all the Gospels, the only witness attested by John and the synoptics (Matthew, Mark and Luke) too. Mary Magdalene, woman of ill or no repute, now foremost witness to the love of God in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

She is there, in John’s Gospel, because she loves. When she finds the tomb empty she lingers, weeping by the tomb.

“Sir,” she says to Jesus (not knowing it is he), “if you have carried him away, tell me where you have laid him.” Jesus says to her, “Mary”; and when he calls her by name, she knows that it is he.

“I have called you by name,” God says through the prophet Isaiah. “You are mine.” (Isa 43:1)

This is the great good news of the resurrection: nothing—not demons, not the death we deal out, not the darkness of our hearts—nothing can separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.

Mary Magdalene, called by name, witness to God’s faithfulness and a great love.