The Second Sunday after the Epiphany, Year C, 2016 – Isaiah 62:1-5; Psalm 36:5-10; 1 Corinthians 12:1-11; John 2:1-12

You shall no more be termed Forsaken,

And your land shall no more be termed Desolate

But you shall be called My Delight is in Her,

And your land Married.

Our daughter Caitlin is newly engaged to be married to a quite wonderful young man, and so we have been thinking a lot recently about weddings. A wedding is a funny thing—because it is both so big and so small. So small: two young people, these two young people, on a summer day in a church in a small town in Virginia. In the midst of the world’s millions, these two and the words they will speak to each other. In the midst of the world’s busy-ness, this one moment in this one church. A wedding is so small.

And it is so big: because in this moment in this church a young man and a young woman give themselves to each other completely. In body, mind and spirit, they give themselves to each other, “to love and to cherish as long as they both shall live.” It is a staggering promise: shall I love this other every day; shall I cherish this other day in and day out, in my waking and in my sleeping, when I feel like it and when I most definitely do not?

Who are we to fulfil these vows that we make? “For the good I desire I do not do,” Paul says, “but the evil I do not want, this is what I do.” Who are we, most days, to love truly, gently and deeply? Who are we to cherish this one, who is so stubbornly, persistently other?

Shall we who in the beginning could not keep God’s one commandment, now keep this vow?

And so a wedding speaks redemption. To love and to cherish till death do us part—to love and to cherish not ourselves but this one who is other: this, ever since Eden and the serpent and the fruit, this requires a miracle.

A wedding is this big. It speaks creation restored. Past the turning away, past the turn to ourselves and away from God, to ourselves and away from untrammelled delight in each other—past the turning away, there is in the wedding this promise. That we may love and cherish; that we may be loved and cherished, again.

You shall no more be termed Forsaken…

But you shall be called My Delight in in her,

And your land Married.

Is it not forsakenness that is the grief at the bottom of all our hearts? It is a grief that has its root in the apple in Eden, that moment of choosing ourselves and not the other, choosing ourselves and not God. We are lonely, longing for God; longing for friendship that is deep and true. We are estranged: that is, Paul tells us, Genesis tells us, the basic reality of the world “sold under sin.”

And estrangement hurts. We are created for love, to live with and for God, with and for each other. That is the crowning act of creation: “and the rib that the Lord had taken from the man he made into a woman and brought her to the man. Then the man said, ‘This at last is bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh.’…Therefore a man leaves his father and his mother and clings to his wife, and they become one flesh.” In the image of God we are made, to live for each other. That is why divorce is so painful: because forsakenness is the grief at the heart of the world.

But a wedding—a wedding is a trumpet-call, our heart’s shout of joy. It is God’s great word of hope. For in the wedding, we mark our redemption. No more let sin and sorrow grow: for the man named Jesus has come.

Jesus has come, son of God in flesh like ours, with a heart to know both joy and grief, to know the love we long for and the forsakenness that we all have to bear.

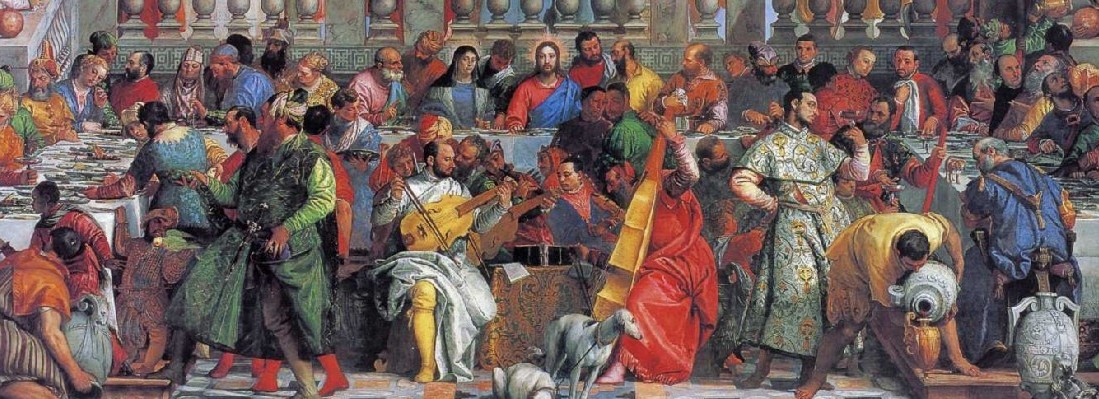

Jesus has come, and he has walked into a small town called Cana, into a wedding feast. And there he begins to announce the good news. For at the wedding there is no longer any wine. The feast has run dry and the joy has faltered—and that is the way it is in this world, our world, that seeks to rejoice and finds itself making a desert instead: Syria and Lebanon and Paris, a world breeding bombs, sorrow springing from the devastated land, and in our own safe city the deserts that can haunt our own hearts.

In this world, when the feast has run dry and the joy has faltered, Jesus comes. And he turns the water into wine.

Rejoice, Jerusalem! Shout, O daughter Zion, for your king comes to you. He comes to you humble and riding on a donkey.

He comes to a small village in Galilee, to a particular young couple there. He sits with his mother and his friends and there, in this small and particular moment, he announces joy to the world, God’s salvation.

Mary knows. She is the only one who does. When the wine had run out, John’s Gospel tells us, the mother of Jesus says to him, “They have no wine.”

At the wedding feast, they have no wine!

At the place of joy, this dryness, this lack where feasting should be.

The world is awry; the table is bare.

“They have no wine,” Mary says to Jesus, for she knows that he is the feast-maker.

He comes to give love to the world that longs for it, and does not know any more what love is.

He comes to give joy to the world that sits in darkness, this people longing for God and forsaking Him.

He comes as water in a dry place, this desert of our souls.

Jesus is the wine that makes the feast.

For he comes into the desert of our own making and he gives us himself as water, as bread, as life. It is his dying that Jesus announces, here on the third day at the wedding in Cana of Galilee, that dying that gives us back our life. Jesus is the wine that makes of our lives again a feast.

“What have you to do with me?” Jesus says to his mother. Strong words, even harsh—they are the words that the demons use in Mark’s Gospel when they recognize Jesus as Lord and Christ. They know that Jesus comes to cast the demons out. These words announce the coming salvation, and its cost.

Mary knows this too. Mary knows who Jesus is and she asks him, here at the beginning of his ministry, to show forth the salvation he brings.

It is a grace that goes by the hard road of self-giving.

To a people that does not know how to love, Jesus gives the gift of love. To the people who cannot give themselves even to their loved ones very well, Jesus gives himself. To us, for us, for these others, Jesus will give his life.

And so the world, washed in his blood, will know again the joy of the feast. All this he announces in the wine at the wedding in Cana of Galilee. All this he gives in the wine at our feast, this Eucharist today. All this we announce, at each wedding feast.

For each one of us, to each one of us, the gift is given. It is this big, and also this small. And so each wedding—Caitlin and Philip’s, Jeff and Jennifer’s, Ruth and Peter’s—each wedding is a sign of our joy. For Christ has come and walked among us even in our forsakenness, when the feast was dry. He has given us himself in love. Therefore we can love again. In him and with him in the unity of the Holy Spirit we can love each other as Christ has loved us—even the one particular other, that one stubbornly other, turning to that one, cherishing that one; giving ourselves for that one each and every day. In each of our lives, the victory of God. In each of our marriages, creation flowering again. It is not easy. It is very, very hard. But so was Jesus’ love. And he walks now with us, each step of our way.

You shall no more be termed Forsaken, we too can say to the other, our beloved,

…but you shall be called My Delight in in Her.

You shall be a crown of beauty in the hand of the Lord.

Amen.