The Second Sunday of Easter, Year A, 2017 – Acts 2; 1 Peter 1:3-9; John 20:19-31

Unless I see the nail-marks in his hands…

Eight days after the Resurrection—this day, that is—Thomas stood in the upper room with the disciples and said, “I cannot; I will not believe.” Thomas is standing where we are now, eight days after that first Easter day, and he says what we might say. Is there anyone for whom Thomas does not speak—who has not said in the face of the Resurrection, in the face of the claim of the risen Christ, “I cannot; I will not believe”? Who among us has not known, in fact, Thomas’ anguish, the impossibility of faith?

For it is, I think, anguish that we hear in Thomas’ words.

Unless I see in his hands the mark of the nails and put my finger in the mark of the nails and put my hand in his side, I will not… I will not believe—

(For my Greek students, an emphatic negative subjunctive; it has the force of an oath. “No way will I believe; I will never believe”).

Unless I see the nail-marks in his hands: It is not just the resurrection that Thomas has trouble with. It is the resurrection of the crucified One. It is the fact of the nail-marks in Jesus’ hands.

Thomas, after all, has seen resurrection before: Lazarus alive again at Jesus’ word, walking out of the tomb in his grave-clothes. “Unbind him and let him go.” He has seen in Jesus the power to give life. He has seen in Jesus the love that weeps at the death that haunts the world. And he has seen the world that God so loves, hate and reject and crucify Jesus in return. Thomas’ anguish is the nail-marks in Jesus’ hands.

And this is true for us too. What is the impossibility of belief? It is the knowledge of the whole sorry mess of things. It is Pilate’s “what is truth,” the failure of governors and priests and kings to be what they should be, to do what they should do, to stand up and speak against the voice of the crowd, and even, really, to care very much about it. The failure of courage that puts Jesus on the cross. It is the people who become a mob; the conviction of righteousness that seeks to silence the contrary voice; the violence of the righteous mob. “We have a law, and according to that law he ought to die.”

Is there anyone who has not looked around at the state of things, the state of our own hearts, and said in his heart, “There is no God”?

This was in fact the chief Jewish objection to the Easter claim. It was a moral, not a metaphysical or scientific, objection. How can the resurrection be true; how can Jesus be the Christ, the son of the living God; how can his Passion be our salvation, when the world is still such a mess? When our own lives are still so unredeemed?

The nail-marks in his hands are the evidence of the evil that we do.

This is Thomas’ anguish. And it is for him—as it is for us—very personal. Where was Thomas, after all, at the cross? Where was he on that first Easter day, when the other disciples were gathered behind locked doors together? He was not there with them in the upper room when they saw the risen Lord. Could it be that he had abandoned his friend? Could it be that he was afraid? St Augustine suggests that Thomas ran so far and so fast when Jesus was arrested that he was still far away on that first Easter evening. Thomas knows the sin of the world, silence and cowardice and righteous violence, and he has seen its power in his own life. He has turned away; he has run away; high-tailed it from the one he knew to be good and true, and he does not hope to turn again.

Where, now, is our God? This is the question raised by the nail-marks in Jesus’ hands, and by every nail that has been hammered into the hands of the world ever since. By the Holocaust; by the ruins of Aleppo, by the Rwandan genocide, by the Armenian genocide; by the hounding this very day in our free country of those who do not tow the party line. This violence that we visit upon each other: The problem that evil raises for faith is acute.

Where shall the Word be found, where will the Word

Resound? Not here….

For those who walk in darkness

Both in the daytime and in the night time

The right time and the right place are not here.

Thomas, like TS Eliot in “Ash Wednesday,” cedes to the world the last word. Not here. The Word is not here.

And here, precisely here—in the place of Thomas’ anguish, the nail-marks and the impossibility of belief—Jesus speaks.

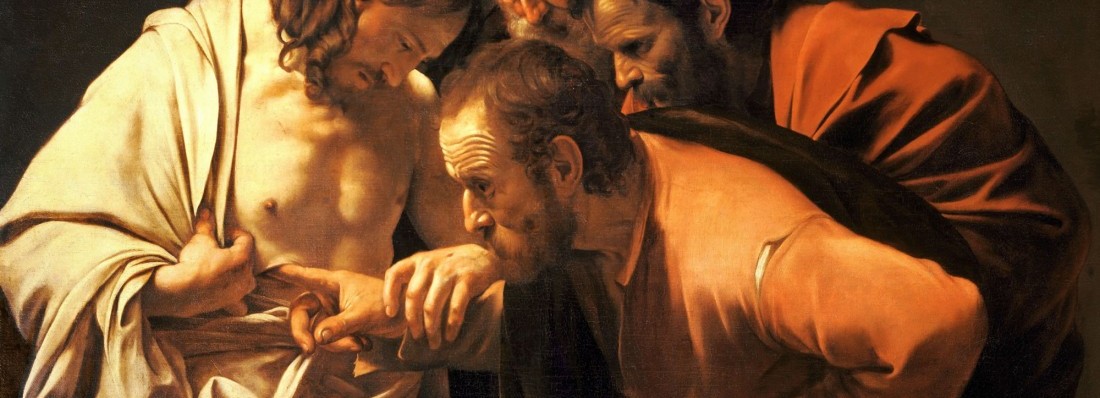

Put your finger here and see my hands and take your hand and put it in my side.

Out of the depths Jesus speaks, and his word is hope. For it is the crucified one who is risen. Christ is raised with nail-marks in his hands: this is the promise. We do not have a Saviour who does not know our weakness, the sin that clings so close, but one who in every way is like us, only without sin (Hebrews says.) One who is like us, and not only like us but with us, who bears the nail-marks—this evil that we do—in his hands. Whose wounded hands rise in blessing; whose wounds speak now not death, our death, but love and in his love our life. In his dying hands the compassion of God; in his risen hands God’s Word. That they may not die but live…for God so loved the world. The Word within the world and for the world. “By becoming man,” von Balthasar says, “God does not speak to himself. He speaks to the world…We are affected in our very selves.”

We are affected in our very selves. It is precisely the harm that we do that is healed in the resurrection of the crucified Christ. This is the good news.

It is when he sees the nail-marks in Jesus’ hands that Thomas says, “My Lord and my God.”

“Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ,” 1 Peter says in a passage that sings in my ears with joy, “who by his great mercy has given us new birth into a living hope through the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead.”

Christ is our hope, this Christ, risen with a gaping wound in his side. Risen with healing in his hands. Christ, who laid his glory by, who died that we no more may die. There is the violence that we do, covered over in his blood with love. Forgiven, my soul, and healed, given back to me in the body and blood of Christ for love.

It is this world God loves and suffers and saves, every rock and tree and child; it is this world that he lifts up out of the deaths that we make for ourselves, out of the sin that destroys, into the joy of the children of God. We—even we—born again into a living hope.

Peace be with you, the risen Christ says to his disciples, this Christ crucified and risen. My peace I give to you. We are addressed by the risen Christ “not only from outside, but are affected in our very selves.” That we may stand in the world as signs and harbingers of his peace, finding in his wounds the power no longer to wound but to suffer and to love.

It is the disciples, Jesus says, who are the witnesses to his resurrection, to his risen wounded hands, this great hope of the world. “Peace be with you,” he says to them; “as the Father has sent me, so I send you.” We cannot see the risen Christ in the flesh. But we can see him in the people who love him and turn to him, who live his love—who are his hands, his wounded and peace-bearing hands—in the world.

Thomas says, finally, “My Lord and my God.” And this is his word of love.

The opposite of doubt is not knowledge. It is love.

It is the love that is faith. It is the love that says, looking upon the nail-marks in his risen hands, “Christ, my Lord.” This one with the nail-marks in his hands: this Jesus, you are my Lord. I will follow you, and your blessed hands will be my song.

My Lord and my God: here in the love of Christ I stand.

AMEN.