What is a “Gospel”? And what is it for, exactly? For those of us who hear the Gospels read in church Sunday by Sunday, or who have copies of Holy Scripture on our bookshelves within easy reach and in understandable modern English, a Gospel is simply a book about Jesus Christ. It is a special book, to be sure, but at base it is simply a book, a textual artifact. We are scarcely aware of how radically fresh and new the phenomenon of a book of the “Gospel” was when it first made its appearance in the latter third of the 1st century A.D., nearly two thousand years ago. For one thing, its physical form was a novelty; the early Gospels were written not on expensive scrolls of prepared skins (like the sacred scrolls of Israel’s faith traditions, or the great literature of the Graeco-Roman world) but on books of relatively cheap paper bound on one side: the codex; just like the books on our bookshelves today. Until the early Christians, codices were only used for business ledgers or for jottings of memos. They were designed to be portable and easily accessible. Scholars used to think the Gospels were written for particular Christian communities who would read them as encouragement or exhortation for the unique situations they faced. They were “epistles in disguise” as one put it. But scholars now realize that the Gospels were intended for an unlimited audience. These codex-bound books “had legs” and they traveled around the Roman world at lightning speed. Their message was not, in the first place, hiddenly about a specific Christian community, but about what they in fact openly proclaimed: the Good News of Jesus Christ for all people.

Last Thursday, the week before Passion Week, my daughter, Deirdre and I went to the Soulpepper Theatre Company production of The Gospel According to Mark. This was a dramatic reading of the King James Version of Mark’s Gospel as performed by the wonderful Canadian actor, Kenneth Welsh. The original idea for rendering a Gospel into a dramatic or theatrical form came from British actor Alec McCowan who, in 1978, memorized and recited the entire Gospel of Mark (all 16 chapters!). I came to this performance with certain questions: how did the first hearers of the Gospel of Mark encounter that book? Did they hear it chopped up into lectionary bits as we now do in our liturgical reading of it? Or did they hear read to them the entire book at one go? What would that actually sound like to hear the full dramatic sweep of Mark’s Gospel at one time without a single pause in the reading? Does something come through in that presentation that might otherwise be lost in fragmentary readings? (To be sure, we might read the book this way, but we never get a chance to hear the book this way.) As well, what would the Gospel sound like delivered in the King James ‘inflection’? Would it sound archaic? And finally, what would the actor (and his director, Albert Schultz) choose to emphasize in the dramatization? What would be the “tone of voice”? These last questions were important because, in the dramatic reading of Mark’s Gospel, the reader/actor seems to assume, as it were, the persona of the imagined author (“Mark”). I wasn’t listening to a “reader”, but felt I was hearing Mark himself passionately recounting the story of Jesus Christ.

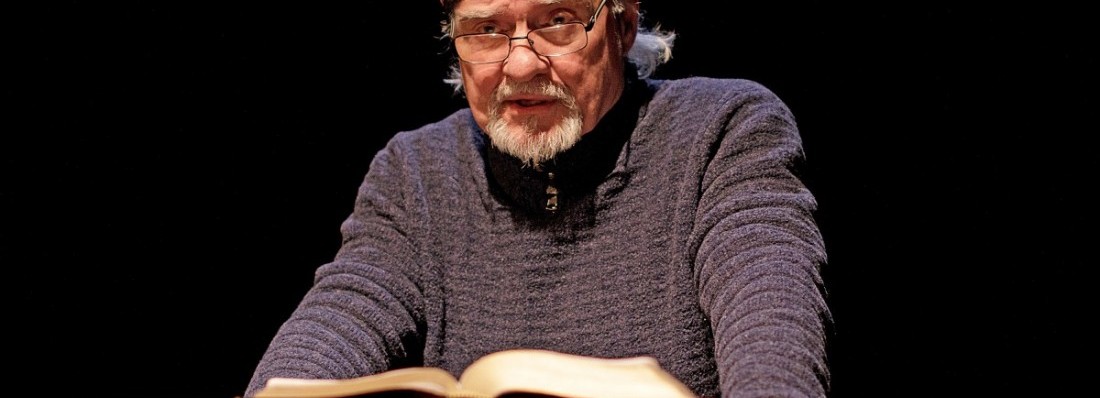

We seated ourselves in the front row of the darkened and intimate space of the Tank House Theatre. Before us, on the floor, stood a wooden lectern upon which lay an opened book (a codex). A dim light illuminated the book. Suddenly, the spotlight brightened and a voice could be heard speaking: “The beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ…”. Before the sandal-shod actor had even reached the lectern, he was already in full flight into the story, a signal intimation of that chief characteristic of Mark’s Gospel: urgency. Welsh never moved from the lectern, but energy and movement was conveyed through his body language, vocal range, facial expression, and especially, pace of reading. But even if it hadn’t been, the energy and urgency of the message comes to full expression in Mark’s language as heard across the entire book. It resounds not only in Mark’s insistent use of the word “immediately” (or, in King James English, “straightway”), but (as became clear in Welsh’s performance) in the constant movement of characters (“again” Jesus goes into Capernaum, “again” the scribes and Pharisees approach), the surge of the crowds coming from afar and “thronging” him, the continuous movement back and forth across the lake, etc. Welsh never slows the pace of the narrative, preserving a sense of almost breathless urgency until, that is, he reaches chap. 13 and the “little apocalypse”, or Jesus’ discourse on the end of days. In this most urgent of all passages, which speaks of terrible coming travails for the faithful, the pace actually slows slightly, the mood darkens, and the repeated final command, “Stay alert! Watch!” is, well, chilling.

The pace of the reading is especially noticeable and a bit jarring at the Lord’s Supper. In church liturgy, these texts are always read or recited slowly and solemnly. But Welsh reads these words with the same sense of urgency as the rest of Mark’s Gospel. Is this how the early church first heard them? It is refreshing to hear this language for the first time read as if it belonged to the larger dramatic sweep of the whole story of Jesus Christ, and not just as an item of special import, set apart to be heard all by itself.

Space limits my commenting on other aspects of Mark’s Gospel illuminated by the Soulpepper production. The King James language does not sound the least bit archaic, but that, I suspect, is largely due to Welsh’s expert and vivid handling of it. The ending of the performance was abrupt and startling, the decision being made to go with the “original” ending of the Gospel of Mark. How odd to end a book with the words: “For they were afraid!” But it is wholly in keeping with Mark’s sense that something truly unexpected and radically transformative had happened in Galilee and Jerusalem with the coming of Jesus Christ, the good news of which was even now reaching all peoples of the inhabited world, amazing and transforming so many whom it encountered.