Good Friday, Year C, 2019 – Isaiah 52:13-53:12, Hebrews 4:16-19, 5:7-9, John 18-19

It is a woman’s voice I hear most clearly, in the cell-phone video, as the people sing.

Sainte Marie, Mere de Dieu, priez pour nous, pauvre pecheurs, maintenant et a l’heure de la mort.

The people of Paris watched – the whole world watched – in grief and shock as flames tore through the ancient house of God. The young woman watches, and she sings her song. Notre Dame, Sainte Marie, Holy Mary, Mother of God,

Pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death.

It is a prayer, and an elegy, the hearts of the people lifted up when they have no longer any power to help. They watch, this week in Paris, there by the burning house of God. And in their watch and in their song there is grief. But there is also something more. There is a beauty in it, a beauty born long ago, born on this day, this Good Friday, born in this cross.

The women watched on this day, too, long ago, on a hill outside Jerusalem called Golgotha.

All the gospels tell us this, and they name the women.

“There were women watching from afar,” Mark tells us, “among them Mary Magdalene and Mary the mother of James the lesser and Joses, and Salome.”

There were many women watching, Matthew says, women who followed Jesus from Galilee and served him, “among them Mary Magdalene and Mary the mother of James and Joseph and the mother of the sons of Zebedee.”

A whole crowd of women follow Jesus as he carries the cross in Luke, and they weep for him.

And in John, the women stand right at the foot of the cross. Mary his mother, and his mother’s sister, Mary the wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene. They were standing there, John tells us. Just this. They watch at the foot of the cross.

What they have seen – Jesus’ mother and his aunt, and Mary Magdalene, the woman Jesus has (John tells us) freed from 7 demons, from a torment beyond the experience of most of us – what they have seen at the cross, these women who love Jesus, does not bear imagining.

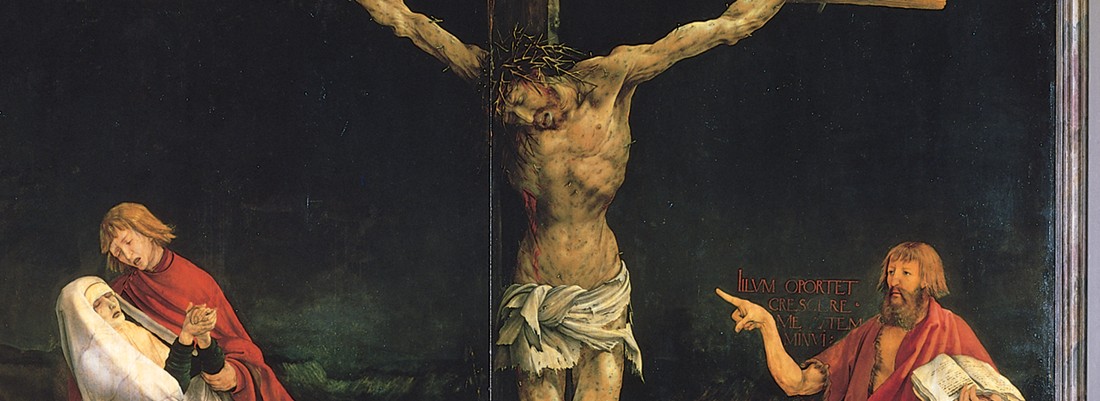

Mary Magdalene, in Matthias Grunewald’s harrowing painting of the crucifixion (in all the paintings), throws herself to the ground and raises her arms to heaven.

Eiyah! Look, O Lord, and see!

It is the old, old lament of God’s people, here, now, again, at the foot of the cross.

Eiyah! Look, O Lord and see

The roads to Zion mourn,…

All her gates are desolate,

Her priests groan,

Her young girls grieve. (Lam 1:4)

In Mary Magdalene’s grief there is all the grief of Lamentations, all the groaning of God’s people under the weight of their desolation. And it is, for Lamentations, a desolation they have brought upon themselves.

My transgressions were bound into a yoke, daughter Zion sings,

By his hand they were fastened together;

They weigh upon my neck;

They sap my strength;

The Lord handed me over to those I cannot withstand.

It is not just the nails in his hands and the thorns crowning his head and the marks of the whip on his back that Mary mourns. It is the larger devastation of which his bruises are a sign and a part.

Jerusalem sinned grievously;

So she has become a mockery.

This is Israel’s lament in the time of Babylon, as the temple burns and the people of God find themselves bound and marched into exile.

“And the soldiers and their officer and the Jewish police arrested Jesus and bound him,” John tells us on this day. The soldiers weave a crown of thorns and put a purple robe on him and as they strike him they mock him: “Hail, King of the Jews.”

…so she has become a mockery.

All who honoured her despise her

For they have seen her nakedness.

“And the soldiers when they had crucified Jesus, took his clothes and divided them and gave each soldier a part.” For they have seen her nakedness

The suffering of Jesus is an ancient suffering, the desolation of Jesus is an ancient desolation, Israel’s suffering, Israel’s destruction in the time of Babylon and again in the time of Rome.

“They took his tunic, too, but his tunic was seamless, woven in one part from top to bottom, and so they said, “Let us not tear it but cast lots to see who will get it.”

“They divide my garments among themselves,” the psalmist cries, “and for my clothing they cast lots.” “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

In the cross of Jesus the devastation of God’s people sounds again. On Jesus’ back, their long exile.

Why? Why this pain, the house of God burning, or slowly abandoned?

Lamentations does not hesitate: We have rebelled, O Lord.

And it is true. Jesus, Son of God, stands before his people, robed in purple with his crown of thorns and his own people say, “Away with him! Away with him! Crucify him.”

Pilate says to the people, “Shall I crucify your king?” And the chief priests answer, “We have no king but Caesar.” Caesar they choose instead of their God. Caesar, who within the generation will send his troops to besiege their city and break down their walls and burn the temple of God.

We have no king but Caesar. Again and again it is true. It is the fundamental problem of our lives. We would be done with God and his word; we would be done with his truth. We would make our own way, follow our own desire. And when the woman saw that the fruit was pleasing to the eyes, and good to eat, and to be desired to make one wise – to know good and evil, to decide good and evil all by ourselves, no need any longer for the word of God, just me in my own wisdom and my own desire – she took and ate and gave to her husband and he ate too.

It has a long history, our choice for our own word over the word of God. But it does not make us free. We only find ourselves with no king but Caesar. The church in lockstep with the culture, finding in its word our god.

The result, of course, is devastation. This wracked body; the house of God abandoned. Jesus sees Jerusalem burning as he goes to the cross: “Do not weep for me,” he says in Luke’s gospel to the women who watch. “Weep for yourselves and for your children. For if this is what they do when the wood is green, what will they do when it is dry?” Jesus sees Jerusalem burning, he sees the children dying; he sees the cost of our turning away.

And on this cross he carries it. Here is the miracle, the unimaginable grace. He carries the cost. On this cross he willingly carries our devastation on his own back.

This is what the cross is. This is the meaning of this day. It is not only our rebellion come to a point. It is the grace of our God, carrying our devastation on his own back. Good Friday.

But he was wounded for our transgressions,

bruised for our iniquities;

Upon him was the punishment that made us whole.

We may no longer have God – we may by our own wish have no king but Caesar. But God has us. He does not turn away. He goes with us into the devastation we have made. He suffers it, for love of us. And on his cross he gives us back to God.

By his stripes we are healed.

God with us. That is what the cross means.

God with us. Emmanuel. It is his holy name.

Did we know, at the birth of the child, in the joy of angel-song and shepherds and magi laying their gifts before the mother and her child – did we know what it meant, this name, Emmanuel?

Did Mary know? “A sword shall pierce your own soul also,” Simeon tells her when she brings the child to the temple.

Mary watches at the cross today, and there her son says, “It is finished.” And the sword pierces his dying side and from it flow blood and water.

His blood, living water, a fountain of living water springing up on this day from his pierced side, for us! For us! Even for this his people, who have chosen Caesar. So that we might come back to him; so that we might take and eat and live. Here the living water bubbles up – right here, at the cross that is the work of our hands. So that we might live and sing to him; so that we might learn to say, “my Lord.” My Lord and my God.

Mary his mother stands there, at the foot of the cross, and he says to her, “Woman, here is your son.” To his beloved disciple he says, “Here is your mother.” Mary the mother of God, not abandoned now as her son dies, but given a new son, here from his cross; given a new child, a whole host of children, his beloved disciples, all the dear children of God. Christ our brother, Mary our mother; Jesus in his dying is making us the children of God.

Outside Notre Dame the people watch and sing in the midst of the flames, and in their song is a beauty born on this day. For he is with us, and his mother is our mother and his God is our God. And in the church the cross stands; the cross stands in and through and beyond the flames. His cross stands and it shines.