The Twentieth Sunday after Pentecost, Year A, 2014 – Deuteronomy 34:1-12; Psalm 90:1-6, 13-17; 1 Thessalonians 2:1-8; Matthew 22:34-46

“Lord, you have been our refuge from one generation to another,” (Psalm 90:1)

Generations come and go. On a recent trip to Ireland I realized suddenly that I knew little to nothing about my family past my own Grandparents’ generation—and this upset me. I can’t help but think that who I am is so tied to who my family was and is that I can’t ever truly know myself without knowing my family. Some people say that you are your family history—that you are, in a sense, the culmination of everything that has ever happened. Perhaps your great, great, great, great, grandfather was abused as a child—who you are today has been formed, in part, by that event, knowingly or not. And the same will be true for my children’s grandchildren—who they will become is already in motion because I am the father of their grandmother, though they will never know me nor I them.

We are born, we live, we die. Time passes—sometimes quickly, sometimes slowly—but passes it does. Generations come and go. Our lives are fleeting—“You turn us back to the dust and say, ‘Go back, O child of earth.’ For a thousand years in your sight are like yesterday when it is past and like a watch in the night. You sweep us away like a dream; we fade away suddenly like the grass,” writes the Psalmist.

Yet, in contrast to the fleetingness of human life, there is the Eternal God: “Lord, you have been our refuge from one generation to another. Before the mountains were brought forth, or the land and the earth were born, from age to age you are God.”

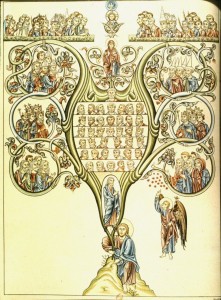

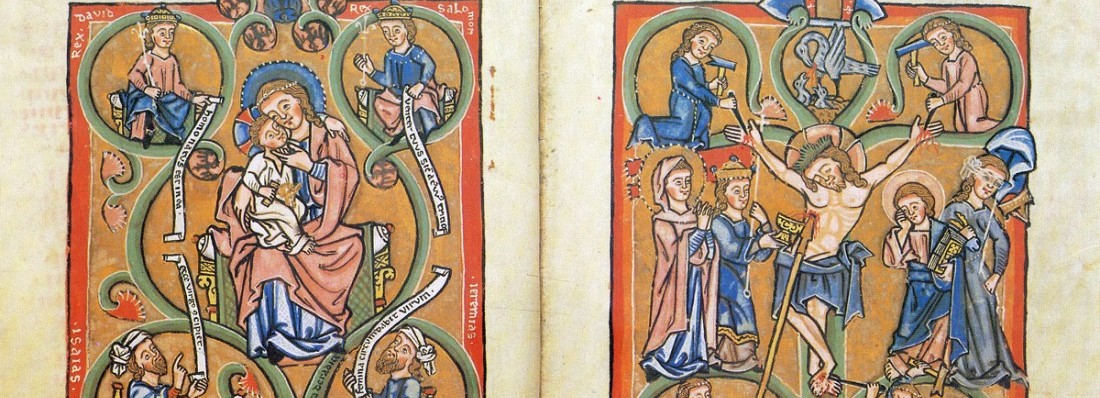

Family is important in the Biblical narrative. From our gospel reading this morning, Jesus asks his opponents, “What do you think of the Messiah? Whose son is he?” We get this during Matthew’s account of Holy Week, that is, the final few days leading up to Jesus’ death on a cross. This question—“Whose son is he?”—we know it’s a question that is central to what is going on in Matthew’s gospel. Note literally the first verse of Matthew: “An account of the genealogy of Jesus the Messiah, the son of David, the son of Abraham,” (1:1). Said genealogy follows immediately: “Abraham was the father of Isaac, and Isaac the father of Jacob, and Jacob the father of Judah and his brothers…” on and on until, “…and Jesse the father of King David…” and on and on again until, “…and Jacob the father of Joseph the husband of Mary, of whom Jesus was born, who is called the Messiah.” Beginnings are important, let us pay attention— The genealogy of Jesus the Messiah, the son of David, the son of Abraham. But if David calls him Lord, how can he be his son? Let us come at this question by way of Abraham.

Our Old Testament reading is the very last chapter of Deuteronomy which is itself the fifth book of the Bible. These first five books—Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy—make up what is called the Torah, that is, the law. It’s an important passage then, because it’s the final 12 verses of the Torah. In it we see Moses who ascends up to a high point from which he can see the whole land stretched out before him, and the Lord said to Moses, “This is the land of which I swore to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob, saying, ‘I will give it to your descendants.’” Fathers and sons. Generations. Inheritance.

Moses has lead Israel out of slavery in Egypt and now stands on the far side of the Jordan. He can see the land but he shall not enter it: “Then Moses, the servant of the Lord, died there in the land of Moab, at the Lord’s command.” Human life has established limits, and here on the threshold of the land of promise Moses’ life ends as it began, “at the Lord’s command.”

We should note also that the Torah essentially begins, in Genesis 12, in the same way it ends in Deuteronomy—with the calling and promise of Abraham: “I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you, and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing…and in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed,” (12:2-3). We might say then, that the whole Torah, that is, the whole law is bookended by God’s promise to Abraham. And it is the whole of this law which hangs on the commands to “love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind,” and to “love your neighbour as yourself.”

“On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.” The word here translated ‘hang’ (kremannymi) is used elsewhere in the New Testament to speak of one hanging on a cross: “Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us—for it is written, ‘Cursed is everyone who hangs on a tree’” (Galatians 3:13). Why did Christ become a curse for us? Paul continues in the same passage, “in order that in Christ Jesus the blessing of Abraham might come to the Gentiles, so that we might receive the promise of the Spirit through faith,” (3:14). The blessing of Abraham. Paul continues, again a few verses later: “Now the promises were made to Abraham and to his offspring; it does not say, “and to offsprings,” as of many; but it says, “and to your offspring,” that is, to one person, who is Christ,” (Galatians 3:16). This is all to say that the whole law, all of God’s promises to Abraham—descendants and land—God’s ‘yes’ to the world, to human creatures, to you and I, to our neighbours here on First Avenue, all of this is fulfilled and secure in Christ Jesus himself, Abraham’s offspring. In the person of Christ Jesus we see most clearly the one Man, on behalf of all mankind, loving God and loving neighbour to the very end.

Raised up on the cross, Jesus, the fulfillment of all of God’s promises to Abraham—the fulfillment of the law and the prophets— actually hung on these two commands.

Recall with me the genealogy with which Matthew begins his gospel, and note that there is something of a rupture: “…and Jacob the father of Joseph the husband of Mary, of whom Jesus was born, who is called the Messiah.” The lineage which runs through fathers who beget sons runs through Mary who begets the Messiah. That is, as Matthew tells us a few verses later, Mary is a virgin and the child conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit: “Look, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and they shall name him Emmanuel,” which means, “God is with us,” (1:23). Leonard Cohen sang, “There is a crack, a crack in everything/That’s how the light gets in.” Indeed, there is a crack in Matthew’s genealogy through which the Light of the World gets in, into our time and space, into our flesh, and in his coming we see the faithfulness of God “from one generation to another.”

The Son of God, descended, and in descending took on our human flesh and entered our human history. And in entering human history took all of history up into himself—from one generation to another. Assuming each and every generation in his own human flesh, what was two is now made one. That is to say, we are members of Christ, and he is one with his Body. For, as Augustine notes, he left father and mother and was joined to his wife, that two might be one flesh (Ephesians 5:31). He left his Father, in that here he did not show himself as equal with the Father, but “emptied himself, taking the form of a servant,” (Philippians 2:7). He left his mother also, the synagogue of which he was born after the flesh. “Therefore what God has joined together, let no one separate,” (Matthew 19:6).

Matthew ends his gospel as he began it, with the language of fathers and sons, and generations. Only this genealogy is of a different sort, according to the Spirit rather than the flesh. The risen Jesus confronts his disciples, his brothers (28:10), upon a mountain and says to them, “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you. And remember, I am with you always, to the end of the age,” (28:18-20).

Let us then cleave to Christ, who is himself our eternal home and who, by descending and ascending, is himself the way. Moses’ death prevented him from crossing through the Jordan and into the land of promise. But Christ’s death is the way by which we who are exiled come home. And we come home to Christ as we come home by Christ, that is, as we pass through the waters of baptism, and as we consume his body and blood, entering into his death and resurrection, and living our lives in and through the very time and space which in Christ has been reconciled to God. For Christ was made man making us his brothers and his sisters, co-heirs of God’s promises made to Abraham. May we who have received these promises not be stingy, not fall into the trap of thinking that they begin and end with us. In Christ Jesus, these promises are received anew by each and every generation. In the church we are one with Christ, may our union with him, one flesh, bear fruit, that is, may our common life together with Christ by the Holy Spirit beget ever new children of God to whom He may be faithful from one generation to another.