Last Sunday after Pentecost: The Reign of Christ, Year B, 2015 – 2 Samuel 23:1-7; Psalm 132:1-13(14-19); Revelation 1:4b-8; John 18:33-37

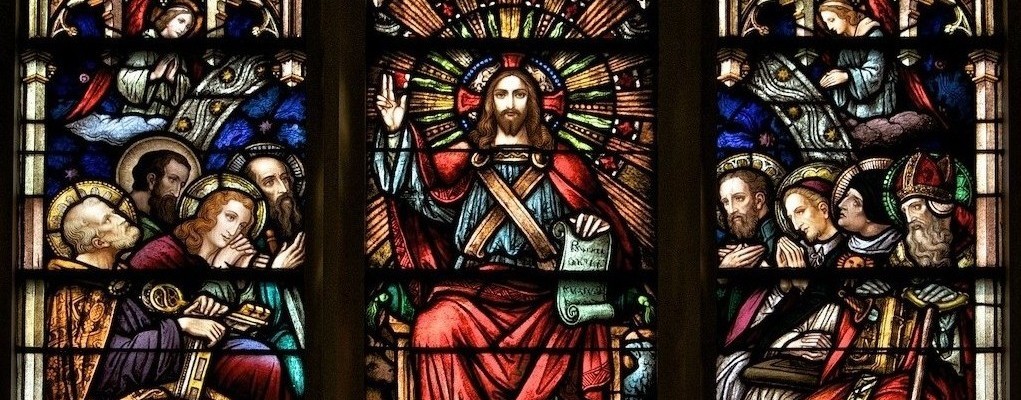

It is traditional, on this last Sunday of the church’s year, before we begin a new year with the Season of Advent – it is traditional to celebrate on this day the fact that “Christ is King”.

I’m not sure the category has much resonance today, however. We know our kings – and queens – simply as one form of the very rich; and they get charged with tax evasion, or drunk driving, or just plain stupidity, like all self-centered rich people and, frankly, like the rest of us.

On the other hand, we do use the term “Lord” all the time. Jesus is Lord!, we are still willing to insist. And every service, we sing the Kyrie eleison, the Greek words for, “Lord, have mercy”. Just there we get at some of the troubling connotations the role of “Lord” still has. We need mercy, in the face of overwhelming and seemingly senseless reality.

A Lord can give mercy, because a Lord stands in the midst of the demands, the sheer and unconstrained power, the wielded sword, hanging over and sometimes letting drop, upon us. Lord, have mercy – we still say this, in hope, amazement, or just plain confused desperation.

I admit to being an anxious person. Perhaps some of it has to do with growing up as a kid in a family where bad things happened. I have seen the arbitrariness of events and of the exercise of human power; the Cold War and the threat of nuclear disaster driven home to us in primary school classroom drills, Viet-Nam, Iraq and their wounds and holes among young people; protests then, protests now, institutions overturned. There was a lot of that in my youth – uncontrolled power, threatening and then spilling out and showing itself for an instant, awfully.

As a young priest in Burundi, Africa I finally succumbed to that lurking and seemingly arbitrary power itself: one day, out of the blue, I was arrested on trumped up charges, interrogated, deported – and I still feel the sense that everything can, in a moment, be taken away, fall apart under the hand of some great force to which I am unknowingly subject.

So yes, I get anxious: events, jobs, churches, institutions, and their impenetrable hearts and impervious judgments and acts. And, of course, children – always, and from the moment of their births ever, without ceasing, pulling at you, and leading you to tremble for their welfare. Finally, needless to say, as you get older, you become like Elijah the prophet (1 Kings 18): looking out over the sea, time and again, there is nothing but a cloudless expanse; until the day, finally, you notice a distant speck on the horizon that comes closer and closer, until now it is a huge and darkened cloud – that’s what it’s like to have the growing sense, when you reach a certain age, of your own death approaching.

So: I am one of those people who wakes up in the middle of the night, and watches all these things parade by my consciousness, and I cry out, “Lord of mercy!”, because I know that all this comes upon us, not senselessly, but nonetheless mysteriously and without escape from the one who owns my life. “Lord, have mercy”. As I’ve gotten older, yes, I think I am learning the truth of one of the most repeated claims of Scripture: “the fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom.” (Prov. 1:7; 9:10; 15;33; Job. 28:28; Ps. 111;10). Hence, “Thou shalt fear the Lord, thy God” (Deut. 6:13).

But, you see, Jesus the King is the one we call “Lord”. And, oh!: how waking up late at night and silently crying out is thrown into confusion by today’s Gospel! Surely, it is one of the most astonishing scenes in the whole Bible.

Then they led Jesus from the house of Ca’iaphas to the praetorium. It was early. They themselves did not enter the praetorium, so that they might not be defiled, but might eat the passover. Pilate said to them, “Take him yourselves and judge him by your own law.” The Jews said to him, “It is not lawful for us to put any man to death.” This was to fulfil the word which Jesus had spoken to show by what death he was to die. Pilate entered the praetorium again and called Jesus, and said to him, “Are you the King of the Jews?” [Jhn 18:28, 31-33 RSV]

You! A bound Jew, already beaten, disheveled, dragged along, thrown onto the pavement. And we call him “Lord”. I imagine Pilate is asking this too in his puzzled way: “Are you the king of the Jews?” – it doesn’t look like it, does it? You standing here, a roughed-up prisoner of your own people? Explain this to me. And when Jesus tries, Pilate still doesn’t buy it: “So you say that you are a king?” How so? Everything speaks against it! And Pilate will make sure that whoever this Jesus is, a king isn’t possibly what anybody will ever think of him as being.

Because whatever we say, the world hurts. And good kings don’t let their subjects wilt away in pain, do they? And when they cry out, “Lord, have mercy!”, they do not stand there bound and broken, with the rest of us!

So Jesus says to Pilate, “My Kingdom is not of this world.” Now, when we hear these words in Holy Week, in the shadow of Good Friday, they are piercing, because they are spoken as an acknowledgement of the world we live in, and we see ourselves in it, and here we look into the face of someone who is not of it, and we mourn that this is what we have done to him.

But today, on this Christ the King Sunday, I think these words have a different tone. Perhaps “kingdom” is better translated, in any case, as “kingship”. So that Jesus is saying, “my kingship is not of this world”, meaning that my being king derives from outside the world, not from within it. My kingship has nothing to do with the powers that you would wield or be overcome by in an instant, in the middle of the night. To say, “my kingship is not of or from this world”, is to say it is from elsewhere; it is to say something very specific: I am king over the world, because I am from outside of this world: I am the maker of it. I am “king” because I am “creator”. And the Lord who stands before us, stands as one who is not “of us”.

Yet, here is just where this king stands. He who is not where we are, is now exactly where we are. This kingship is real because it has been transferred from its rightful place outside of our world, to where it should never possibly stand, inside of it.

What does this mean? I can barely understand it! If not of this world, then consider the chasm that needs to be crossed, Creator to his creature! A gulf so great as to defy imagination – except that this is exactly where, deep in its canyons and abysses, we hurl our tremblings and cries. Through all this, the King makes his way, and comes. Not of this world, but into this world, that is not Him, that cannot contain him, that is infinitely different from Him.

This is expressed in various ways in Scripture: Karl Barth, the great Swiss theologian of the last century, said that the story of the Prodigal Son captures this divine passage of the king in all of its mystery, so astonishing that it seems to hurt: a beautiful child, who leaves all his wealth and his home and family, and travels to a “far country”, where all is nothing but waste and filth, and into which he is mired…then, with deep internal exertions, to return. Or, again, there is the story of King David, who, at the height of his prosperity, is overthrown… by his own son, Absalom, and rejected by his own people and forced to flee Jerusalem just to survive; and as he leaves, his supporters weep; something that David then does himself, on his sad return – rebel son dead, his nation decimated. Whatever David said today at the end of his life, our reading — Yea, does not my house stand so with God? For he has made with me an everlasting covenant, ordered in all things and secure. For will he not cause to prosper all my help and my desire?” (2 Sam. 23:5) – when David says this, it cannot mean what we think it means – David knows better what a king is, who is the Lord from heaven: that is, that “though he was in the form of God, he emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, becoming obedient unto death” (Phil 2:6-8), for “he came to his own home, and his own people received him not” (John 1:11).

Oh, I am other than you, Pilate, Jesus says; other than your worries over whom to please; other than your wife’s anxious dreams; other than the fears of priest and people. Yet I, the Lord, your Maker, completely other than this world where you do your business for good and ill, and are so often overcome, I the Lord, though I am not part of this world, I stand before you here. That is to say: “I have come to you.” I have had to do this, and I have done it. I have come.

The whole basis of the Christian faith lies with this fact: that the God who made us is not one of us, is Other from; yet He lets us be, and comes to us.

He gives us free life, freedom, free will, free movement, free-standing being. Why? In order to come to us face to face, as another Person. In order, that is, to love us. For there is only love in coming.

Everything about Jesus’ kingship, and his kingdom, about Jesus the King – everything about Jesus as our Lord – it’s all about his “coming”. Jesus, the Lord, is the “coming one”; not in the sense that he is not yet here, but in the sense that his here-ness is in his coming-to-us. Hence, our Christian focus so often, as today and in Advent, on his “return” – “Look! He is coming in the clouds!”, John says today at the beginning of the book of Revelation (1:7); and he ends the book, the whole book of Revelation and hence the end of all the books of the Bible, by shouting out, “Maranatha!”, which is Aramaic for “Surely I am coming soon.” Amen. Come, Lord Jesus!” (Rev. 22:20).

The King comes, our King is a coming King, because, “My kingdom is not of this world”; “yet God so loved the world, that he… sent His Son into the world” (John 3:16, 17). What does this mean? The Christian Gospel has no explanation of the mess of the world in a way that could ever resolve our sorrows and dissatisfactions.

For the Christian Gospel is supremely realistic: it describes what is the case; it knows that no explanation can make what is really a wound feel like a joy, or what really weighs down the soul seem like a release.

But what the Gospel does reveal, in the midst of a real world, is the fact that there is such a thing as love given in freedom; such a thing as love, that underlies the world, that comes from beyond this world, that meets this world, that enters the midst of the whole world’s reality. And even so transforms it.

How could it be otherwise? The Lord is Lord of the world, by letting it be in existence, by letting each of us live, and, in the midst of that undeniable reality, with all that it brings and contains, coming to us in love. Coming to us there. Coming here. That is how God rules the world He has made. That is the Lord’s power. By coming into the midst of what we have made of ourselves — of our confusions, our sins, our killings, our questions, our weaknesses, our joylessness and our joys, our strengths and illnesses, our grasping and our dying — God rules by making this — which we have made in freedom — the place He comes into to make His own, His very own, in love. That is the world; and that is the God of this world, our Lord.

So Pilate takes the King, not “of” this world, and makes Him suffer just as the world does. But unlike the world, the Lord of the world suffers in love, infinite and awesome. The Maker of the world, suffers in love for the world. “Our God reigns from a tree”, as the ancient poet Fortunatus wrote, in a hymn that is rightly still part of our Hymnal (186). God rules, God is King, from a tree; because God has come into the world that he made, of plants and animals and trees (Gen. 1:11), and made the landscape we have ravaged His own garden.

When you are young, who will you follow willingly? You will follow the one you can trust most completely; the one who comes to you, so fully, so deeply, so far that even death is the place he ventures. “Lord have mercy!”, I cry out. But he has come – he is already there — before I speak. Lord have mercy, yes; but only because, Maranatha: Lord Jesus, come. Amen, and amen!