Eve of Holy Cross Day, Year B, 2015 – Numbers 21:4-9; Psalm 98:1-6; 1 Corinthians 1:18-24; John 3:13-17

Holy Cross. We are so used to hearing these words together that I’m not sure we hear what a strange pair they make. The cross: Rome’s most terrible sentence of death. Ugly, slow, agonizing; a public humiliation. And now we call it holy? It’s an extraordinary claim: that in Christ even the cross is made better. That this world’s worst may be made better…in the death of Jesus the Christ. Do we get it? I am not sure.

This week I saw a sign as I was walking down the Danforth.

“Make your day better: Buy a graphic tee!”

It struck me this week–because it speaks to the deep-seated longing that we mark on Holy Cross day. Make your day better…make your life better…make your world better. Surely that is what we all want. Such an outpouring of compassion there has been, and of anguish, over the past couple weeks, since the picture of the little boy dying on the other side of the world hit everyone in the heart. Make this day better. Let there be peace. We long for the better day.

It is the other part of that sign on the Danforth that is the problem. Because it is not going to happen that way. No amount of graphic tees, no amount of buying them, can make this the good day, the good world for which we long.

And there is, it seems to me, a terrible kind of blindness in the way our real pain for the suffering of the Syrians coexists in our daily life with this other thing, this turn to ourselves (make YOUR day better); this desire to seek a better day in the things that we can have.

It is not here that happiness is found: not while a boy lies dead on the Turkish shore; not now and not ever. Because the tee bought for me and my better day ignores the pain that is out there—and so it does not speak of love; there is in it no sign of our love for the suffering people, and it cannot make our day, or anyone’s, better.

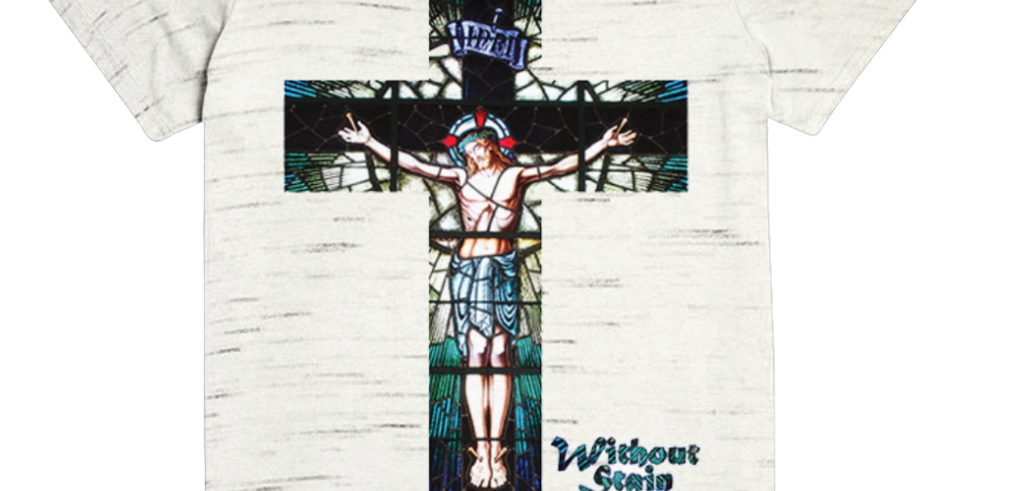

Jesus offers us another way. Jesus offers us a different sign, to wear like a t-shirt over the heart. Jesus offers us the cross. It is the sign that is true, for it does not ignore the pain that is out there, even as it announces the better day.

Just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness: this is where the cross begins. It begins in the place where the people reject God. It begins with the grumbling we do against the difficult purpose of God. “Why have you brought us up out of Egypt to die in the wilderness?” God’s people say. “For there is no food and no water—certainly no graphic tees—and we detest this miserable food.”

I have always found that line funny: there’s no food here and it tastes terrible. It is a ridiculous complaint: God has delivered them from slavery in Egypt and brought them safely through the Red Sea; God has given them manna from heaven and water out of the rock. And they look back to the fleshpots of Egypt, the fish, the melons, the onions and garlic “and now there is nothing at all but this manna to look at” they say, in Numbers 11.

Freedom…or garlic? Which would you choose?

It is ridiculous—and it is human. The rejection of God’s purpose never does make sense. For no matter how difficult God’s way is (and often it is indeed difficult, leading us into a wilderness on our way to worship our God), God is with us always. “Our God is the one who can part the Red Sea”, a priest said to me in Cuba, in the days of Castro. Our failure, to trust, to follow, to leave behind the old life that binds us, is ridiculous—and worse; it is poisonous, in the face of God’s faithfulness.

“Then the Lord sent poisonous serpents among the people and they bit the people, so that many died.” And the people said, “We have sinned against the Lord” (Num 21:6-7, paraphrased).

But it is human.

The newspaper cries pity for the Syrian child, and beside it the sign says “Make your day better: buy a graphic tee.”

And the serpent creeps into the garden, into the wilderness, calling our hearts away from God’s purpose, calling our hearts away from God’s love, turning us in on ourselves. This is sin. And it poisons our lives.

In the wilderness the people die. Is there then any hope?

“As Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so the Son of Man must be lifted up” (John 3:13). If our inability to follow in God’s way poisons our world; if the cry of the sweatshops and the starving and the fleeing and the lost—a whole culture desperately seeking happiness in a t-shirt—if the cry of the lost still rises from earth to heaven, that is not the final word. For God hears the cry of his people, then and now and always. Precisely in the place where we are lost; precisely in this death we mete out to ourselves and to each other, this wages of sin, God comes to meet us. The Son of Man is lifted up like the serpent in the wilderness, God’s love meeting our agony, this harm that we do.

For there is nothing more cruel than a cross. The cross stands over our world as an indictment, sign and sum of all the evil that we do. Here is the suffering of the Syrians; here is the suffering of the Jews; here is the pain of all the crucified people since the world began and also the will of the world to crucify and to ignore: here it is, written on this wood.

And it is here that God meets us. On the cross God’s Son raised up, the body of Jesus, the beauty of Jesus now covering this wood: covering our sin with his love, covering our pain with hope.

What wondrous love is this, O my soul, O my soul? The hymn sings.

What wondrous love is this,

that caused the Lord of bliss

to bear the dreadful curse for my soul.

On his back bearing the harm that we do, covering our pain with his love.

Holy Cross! Can there be any name stranger and more wonderful? For the instrument of death has become the instrument of God’s love, and death is swallowed up in victory.

Holy Cross. It is a contradiction in terms. And it is the sound of hope. For it is so true. It does not ignore the pain there is in this world of ours, the harm that we still do. It is to that pain that it speaks. For there, precisely there, the face of Christ rises too, suffering with us, suffering for us, radiant with grace. Did e’er such love and sorrow meet, or thorns compose so rich a crown? Sorrow and love together, in the face of Jesus Christ. That is why the cross is beautiful. For the harm that we do is not the last word, and there is a greenness that leaps at the heart of things.

There is such joy in the cross. Pray that we may wear it always as a sign over our hearts; pray that it may be written on our lives. Lift high the cross. May we find in it this world’s better day.