The third Sunday after the Epiphany, Year B, 2015 – Jonah 3.1-5, 10; Psalm 62.6-14; 1 Corinthians 7.29-31; Mark 1.14-20

“Come, follow me,” Jesus said, “and I will make you fishers of men.”

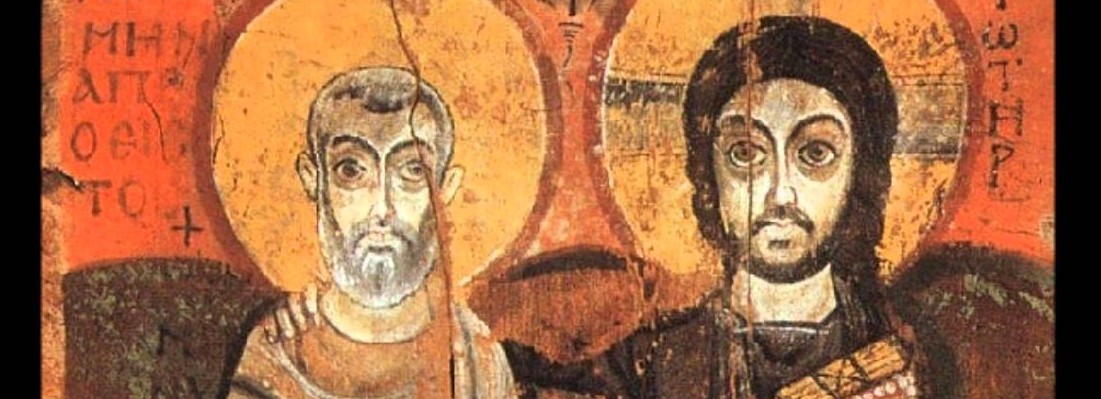

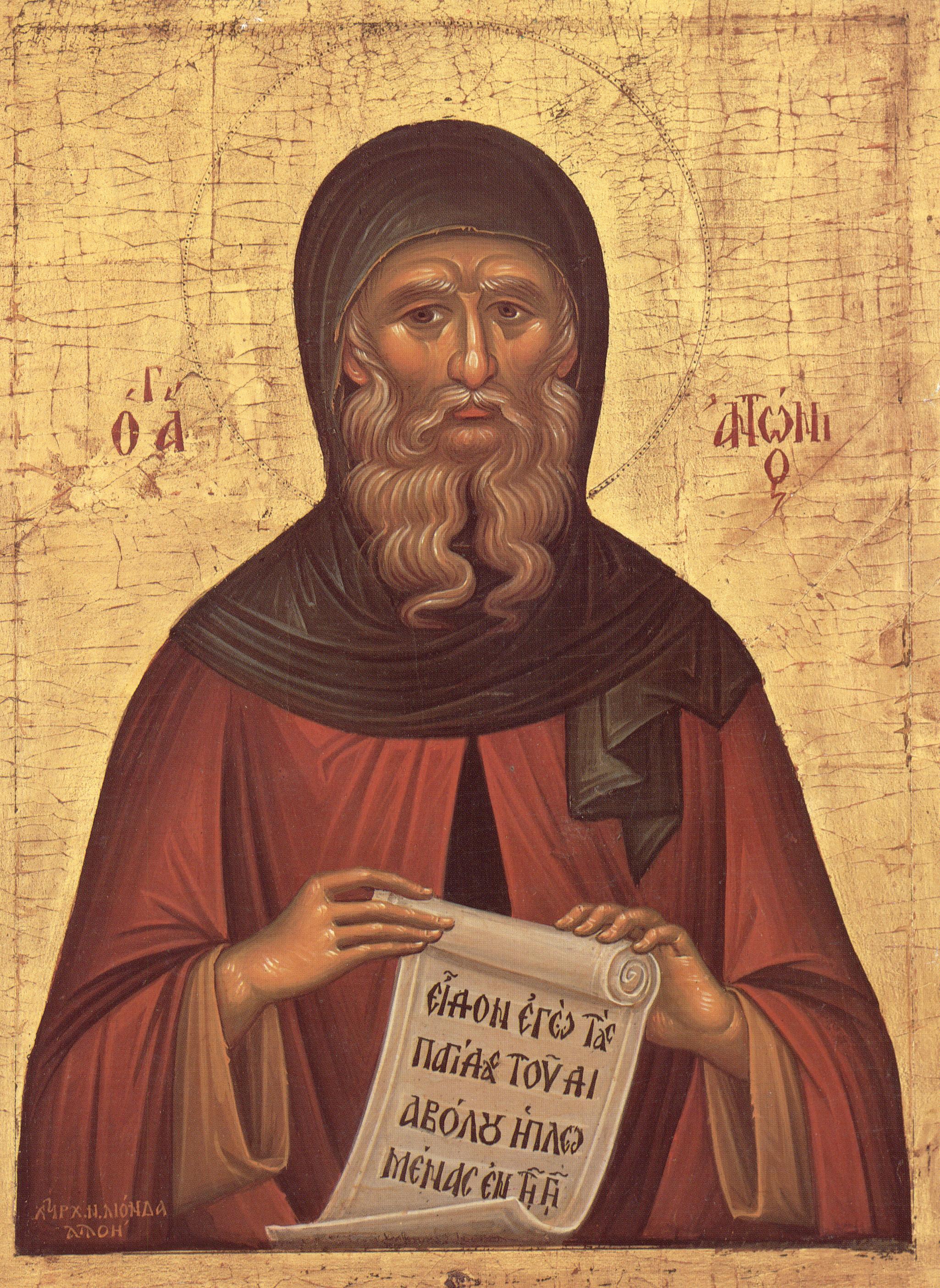

The desert fathers and mothers were men and women who, beginning in the 4th century, left their towns and families and livelihoods and journeyed out into the deserts of places like Egypt and Syria. Anthony the Great, for example, was by no means a rich man but when he heard the Gospel read in church he took very seriously the words, “Go, sell all that you have and give to the poor and come…”. Likewise, Syncletica of Alexandria was from a wealthy family and after the death of her parents she gave all that had been left to her to the poor, and with her younger sister abandoned the life they knew to reside in a desert crypt, adopting the life of a hermit. These are but two well known examples from among the thousands who made this journey. “The desert had become a city,” wrote St. Athanasius.

St. Anthony the Great

Notice a similar sort of detachment in our readings this morning. Simon and Andrew “immediately left their nets and followed him.” James and John, well they did the same, only they also left their father Zebedee standing in the boat. Moreover, these four men didn’t have a whole lot of room for consideration. Should we follow Jesus? Is this a good idea? Where will he take us? Think of all we’re leaving behind! A similar note rings from the words of the Apostle Paul: “from now on, let…those who deal with the world be as though they had no dealings with it.” What trust; what detachment; what freedom!

The immediacy of the disciples response tells us something important about what it takes to follow Jesus—we needn’t wait until we have it all figured out to get started.

For some this will come as a relief. For others, the more risk averse among us, this can be terrifying. For good reason, following Jesus is both of these things—a terrifying relief. And as such, part of what it means to be Christian is learning to live out-of-control. Learning to detach from the world so that we might follow Jesus completely, placing our trust in him above everything else—our jobs, our money, our health, our families, ourselves. “For God alone my soul in silence waits; truly, my hope is in him. He alone is my rock and my salvation, my stronghold, so that I shall not be shaken,” writes the Psalmist.

The reason for this detachment is because the world as we know it is fading away, writes Paul. It’s fading away because, to quote the very first words from the mouth Jesus in Mark’s Gospel: “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near.” Something has happened as a result of which the world is now a different place—in Jesus the reign of God has come near. This means that the day of salvation is now. The day which Moses and the prophets spoke of has come, and that day looks like Jesus. Thus, we are called to “repent and believe,” because “the kingdom of God has come near.” To repent and believe is to live in light of the reality of the cross and to orient our whole life towards Jesus, something we learn to do in the process of doing it. It is to allow the king of love to be enthroned in our hearts and minds, to take undivided possession of our will and make our very bodies the temples of the Holy Spirit. The light has dawned, wake up! Furthermore, the Way to this kingdom is Jesus himself. Detachment from the world then, is for the sake of an attachment to Christ who calls us to leave what we know and follow him.

At the start of Jesus’ ministry what does he do? He immediately summons these men to be his disciples. Jesus doesn’t descend as some sort of heroic and powerful figure who sets out to accomplish his mission by himself. Immediately other people are brought into the fold. And we’re not talking about the best and the brightest either. These are fishermen after all—rustic, common, unsophisticated. Those without education used to instruct the nations. And it’s in this way that the work of God begins to blossom and expand in the world first in the life of Jesus, but then—like and because of him—in the lives of those who have been called and commissioned by Jesus. That the kingdom of God has come near means that God has not abandoned his good creation to the powers of sin and death. In Jesus and his church, God’s saving work is being worked out in human lives, in human history.

But of course, this attachment, this loyalty to Christ Jesus opens ones life up to a certain strangeness. In fact, it earned early Christians the reputation of being atheists for refusing to worship the gods of the pagan Roman Empire. For example, in the middle of the 4th century Julian, then Emperor of Rome, wrote a letter to Arsacius, the pagan high priest of Galatia saying: “It is [the Christians’] philanthropy towards strangers, the care they take of the graves of the dead, and the affected sanctity with which they conduct their lives that have done the most to spread their atheism,” (as quoted by David Bentley Hart in Atheist Delusions). As far as Julian was concerned, Christianity was spreading at the rate it was mostly due to the utterly novel practices of showing charity to strangers and a belief in the sanctity of each and every human life, no matter how poor or disfigured. The gospel opened people up to a new moral horizon, previously unimaginable, which forever changed the world. Early Christians also held to such unthinkable practices as fidelity within marriage, treating slaves with respect as brothers/sisters, treating women with dignity as equals, not scorning and excluding the poor but seeing in them the face of Christ, and refusing to expose infants (a practice that involved leaving new born children to the fate of the gods by exposing them to the elements and whatever else may come)—but I digress. My point is that for those early Christians in pagan Rome, following Jesus entailed resisting and rejecting what were otherwise run-of-the-mill, normal practices. And, for many of them, this came at a cost, sometimes an extraordinarily high one—their life. Other times it just meant being peculiar, weird, and unpopular.

Are we living in very different times now? Does following Jesus for us, like our brothers and sisters before us, not demand a similar sort of reappraisal of our human situation in light of the good news of the kingdom of God? I’m thinking of some cultural norms that we perhaps may take for granted: consumerism, the pursuit of power and social prestige, a sexual ethic with no end other than our own gratification and self-realization, and racism (here in Canada, I’m thinking particularly of the trauma faced by our Aboriginal brothers and sisters). Does following Jesus disrupt any of this? Should it? Have our imaginations been formed in such a way that we think even to ask these sorts of questions?

Perhaps we live in a time and place where our lives are not at stake, but at the very least following Jesus ought to make our lives a bit weird. Let us own this weirdness rather than be embarrassed or feel the need to apologize for it. Because Christianity is weird—it opens up an entirely new way of life, one given its character, shape, and direction by the One who calls us.

So, you and I are called to live unattached to the world in order that we might live attached to God in Christ. However, this doesn’t mean a wholesale rejection of the things of the world as “bad”—though, as with pagan Rome some things ought to be rejected outright. The good news of the kingdom isn’t about escaping this world for some sort of heavenly one, after all. It means rather that we don’t know how to see the world rightly until we discover how to see it rightly in Jesus. As such, the detachment from the world required to follow Jesus actually opens us up to a truer, more faithful attachment to the world—we might call this attachment love. Fittingly, this describes God’s relation to the world. He is not bound to the world, to you and I. He has not painted himself into a corner whereby the only way out was the way he took. God in Christ attaches himself to the world, and the world to himself, because God is in the first place totally unattached to the world and thus totally free to love. This is the doctrine of Creation—all things have their being not because they have to be but because God is love. You and I are and continue to be because of the creative and sustaining love of God which we come to see most fully in Christ Jesus on the cross, God for us. God on our side, not because he has to be but because he is free to be—this is the love of God.

In a similar way, in following Jesus you and I are freed up to truly love the world. And fittingly, this describes the mission of the church—not to be closed off unto ourselves, but to be for the world, as God in Christ was and is. In John’s gospel right before he is arrested Jesus prays for his disciples, not that they be taken out of the world but that they be protected from the evil one, for they have been sent into the world as one, just as the Father and the Son are one. Why? So that the world may believe.

For those of us here in the late modern West, the world has changed. Church buildings in the centre of town and on prominent street corners are emptier than they once were. Our neighbours may no longer believe what we believe, Christianity seems to be fading away, and as such our faith has been “fragilized” because it is no longer self-evident. Actually, perhaps it’s not so much that modern Western folks no longer believe as it is that Christian belief seems strange and unnecessary. In such a landscape, it is tempting to think that what we believe must change. This is the mistake that liberal Christians often make—changing a few beliefs or doctrines to make Christianity more palatable, we think, to modern Western people. But it is not what we believe that must change, it is rather how we believe.

Perhaps then the lives of the desert fathers and mothers provide a fitting model of Christianity for those of us situated just here. I am not suggesting, of course, that we ought to head out into the wilderness in some sort of new monastic movement. I mean only that in these lands where the old Christendom has mostly faded away, the devotion of these ancient men and women to charity and to prayer, in willing exile from the world of social prestige and power, may perhaps again become a model that Christians will find themselves compelled to emulate (David Bentley Hart). Jesus has called you and I to follow him. May we be willing, like those first disciples and like the early Christians, to be just such a peculiar people, on just such a peculiar journey, for the sake of the world. Amen.