Sunday of the Passion: Palm Sunday, Year C, 2016 – Luke 19:28-40

All of our worship on Sundays is a kind of theater, wherein we act out a drama that is given us by another playwright, a divine one. But nothing is more theater-like than Holy Week – a story unfolds each day, as we move from Palm Sunday today through the Passion into Easter Sunday; our prayers fall into step like a Greek chorus, watching, pondering, being swept along; at points we even become the actors, literally speaking from the script of the Gospel, as we have just done. But since the playwright in this case is indeed divine, is God himself, this is not a drama like any other, to be seen, perhaps even moved by, but then from which to remove ourselves back to real life. This drama stands on the threshold between our thinking and real life itself: it is, as it were, the soul of our “real life”, which we have the chance to gaze at, as in a mirror: our own deepest soul! Christian worship is not simply praising God; people often misunderstand this, I think. It is an unveiling of the truth; so that, seeing the truth, we may be changed. Christian worship, and here more than any time of the year, is not what we bring to God; it is God’s gift to us. Which is why it demands patience and attention, receptivity and engagement – not simply feelings.

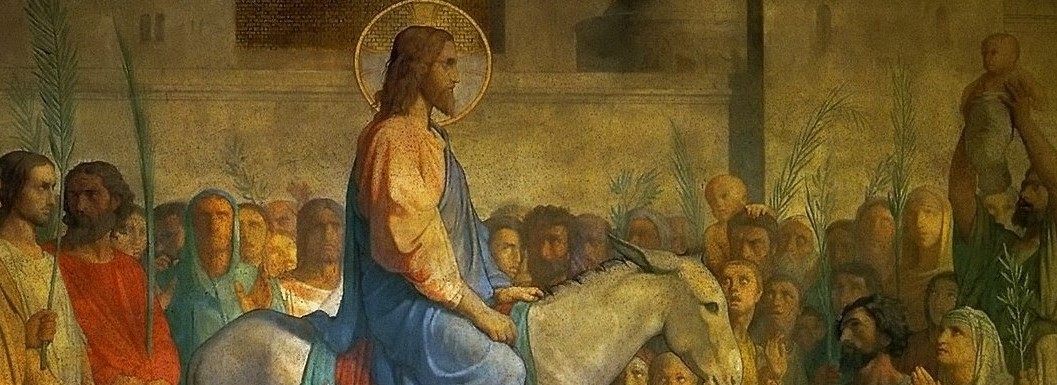

The drama begins today with Jesus entering Jerusalem, riding on a donkey’s back, welcomed by crowds of singing disciples, who rejoice and praise God, as they receive

“the King that cometh in the name of the Lord” (Lk 19:38). We see the Pharisees urge Jesus to silence these claims – no talk of kings here, please. But Jesus answers them in an odd way: “I tell you that, if these people should hold their peace stones would immediately cry out” (40).

What is odd, to me at least, is that Jesus thinks that rocks could ever speak. This, I think, is key to the drama: rocks with voices.

Now I don’t really know what this means, key though it may be. In the 19th century, when John Ruskin began writing his famous works of art criticism, on Venice and the rest, the literary world gushed that he had “made the stones to speak” (cf. Proust’s comment). But that’s not what is going on here. The Bible tells us that rocks can indeed give voice to something. The Psalms tell us that the hills “rejoice”, and even clap their hands before the Lord (cf. P. 65:12; 98:8). And precisely in a promise of redemption, Isaiah writes:

“For ye shall go out with joy, and be led forth with peace: the mountains and the hills shall break forth before you into singing, and all the trees of the field shall clap [their] hands.”

(Is. 55:12).

St. Augustine sees this as the central work of creation: in one of his favorite phrases, he tells us that everything in the universe, in “the heavens and the earth,” stands before us, in a “great voice”, proclaiming to us “Deus me fecit! God has made me!” (cf. Sermon 68.6), or to God himself, “You have made me!” (cf. Enn. Ps. 148). If this is so, then surely, in the face of their King, the stones will cry out, however it is they do this.

But there is a darker side to this too.

The stones will speak, to be sure; but they speak also of what has gone terribly wrong.

“The stones will cry out” against Israel, the prophet Habbakuk writes (2:11), recoiling at Israel’s sins. And even Jesus, just here in Luke after his great entry into Jerusalem, literally “weeps” over the city, and predicts Jerusalem’s utter destruction: “they will dash you to the ground, you and your children within you, and they will not leave one stone upon another” (Lk. 19:44). The stones too, that is, will weep, and will be ground down with the people’s muzzled tongues.

Deus me fecit! God has made me! Yet we too will be destroyed, the rocks must admit. So ”the mountains quake before him, the hills melt; the earth is laid waste before him” (Nah. 1:5), and the people cry out to the mountains “fall on us!” and to the hills “cover us” (Lk. 23:30). Cataclysm is something that swallows up the living and the inert, beast and stone together.

So, the rocks will sing or sigh or fall silent together with men and women in the face of their own fates. It is no surprise that, examining the world – earthquakes, droughts, floods, landslides, and then, as knowledge of the wider universe increased – vast spaces, dried out planets, colliding galaxies – it is no surprise that many Christians came to see the rocks too as bound up with that twistedness that we see in our own hearts. (Cf Thomas Burnet). Is not the universe itself caught up in some horrendous spiral into nothingness?

The voice of the rocks, then, with which this drama opens as a hint, points to something profound; to a deep-down thing that is going on and that encircles us and founds our steps, and echoes in our ears. St. Paul puts it this way: “We know that the whole creation has been groaning in travail together until now” (Rom 8:22). Groaning together, with us, and us with it Bound together in crying forth, in unthinking praise and in well-grounded sorrow both. It is a deep down thing that we enter.

There often seems to be a huge distance that separates the church and the rest of society these days. People watch us as we enter Holy Week, if they watch at all, and see these strange gestures that we engage, like some immigrant native group, enacting the rituals of their homeland far away and in another world. Palm branches, chanting, kneeling, reciting. How odd! Like talking rocks!

But the deep-down thing is real; and real, I think for everyone.

There is yearning for the king. A yearning so deep, that it seeps out even from the seams of the earth’s crust, just as from the joints of tired people. Maybe that yearning crosses the chasm between Christian Church and not-Church. I think it may.

And I note this, not to say anything about evangelism and how to do it – though there are implications to such a yearning for the king. And because a King is yearned after, even by the rocks, there are also implications here about church and society more broadly. But I’m really just talking about what you and I are up to as we enter this week. We watch the King enter Jerusalem, people shouting out – and we join them in this drama. Yet we also realize how poorly any of this will be grasped, how quickly it will turn to something else, how much you and I and all of us together scatter, run away, repudiate. We enter this week yearning for the King; yet we are brought face to face with the fact that we do not really welcome him.

So where does our yearning lead us – crying out, and then, like stones, being dismantled?

A wonderful English Dominican from over 100 years ago, Vincent McNabb, wrote once that the greatest achievement of a human society – that is to say, the most beautiful acheivement, the most glorious, the most intricate, the most work a society can do! – the greatest achievement of any human society is peace. And oh, what it thus costs us!

It is interesting that this is just what Jesus indicates after his entry, as I mentioned: “When he drew near and saw the city he wept over it, saying, ‘Would that even today you knew the things that make for peace! But now they are hid from your eyes.’” (Lk. 19:41-2).

After speaking to the stunning accomplishment of social peace, when it happens, McNabb goes on to say, however, that there can be no peace in a society without peace in one’s own heart. That is the place the sheer labor of peace must begin. It isn’t a sentimental claim either, but, in a way, an obvious remark. We are so naïve – and our society so deluded – into thinking that we can forge a peaceful civil sphere, when we are at war and awry in our own spirits. I say this to my shame, in my own small realms of life: far too willing I am to settle for “getting along”, for jerry-built structures at work, but also in my family. “I’m ticked off, I’m unsatisfied, I’m angry even – but this will do, this arrangement, things will sort themselves out as we go along. I’m not going to push things or sort them all out; it’s too complicated; too much work. I’ll ‘manage’ it.”

But that is simply false.

There is no “managing” peace. And we see it all around us.

How, how I need more than that! How much we all do! And so we yearn¸ and our yearning takes us somewhere: to the edge of a great gulf, darkened in its depths, into which the rocks tumble with a fading echo.

I am yearning for the King; I am yearning for peace; I am yearning, but do not know where it is! Every one of us. Our common life. The deep-down thing that drives us to face something we cannot make out.

As I said, that is the drama we are walking into today; not as a play, but as the mirror to our soul and its true destiny.

And there goes He who has so confused me. The king I do not understand. Into that place, where my yearning is simply lost. Where the stones go mute. He goes into that place., beginning today. I am today not preaching an outcome, although the outcome is promised. I am preaching about the nature of this outcome: that is, that it comes from God. We yearn; but then we must receive – everything. “For I tell you: God is able from these stones to raise up children of Abraham” (Mt. 3:9). That is, in a way, how the Gospel begins, in the words of John the Baptist. And the Gospel ends with a group of confused and yearning women, who go to a garden tomb, where they find a “stone had been rolled away” (Lk. 24:2).

You see: we cannot know what grace is until we enter this week. Maundy Thursday; Good Friday; Holy Saturday, and then… It is why we do it every year, so that we do not forget, so that we do not slip back only into a dissipated yearning only. like a tired dog that follows us around. No…. grace is somewhere else – from outside of us; from beyond us; to be given to us from the one who made Adam from the dust of rocks and stones. Only He, the maker of heaven and earth can take us there. Procedamus in pace: let us go forward in peace.